<a href="http://www.flickr.com/photos/michaelcr/5891138645/">Michael Rosenstein</a>/Flickr

“Live Free or Die” is the motto of New Hampshire—and in the run-up to the state’s first-in-the-nation presidential primary every four years, Americans are reminded ad nauseam by presidential candidates, pundits, and reporters of the independent streak of New Hampshire voters. They’re usually referring to New Hampshire’s “undeclared” primary voters, the roughly 40 percent of the electorate who haven’t registered with either political party and who, in theory, could wait until as late as Election Day to decide how they’ll vote. Typical ways of describing this bloc of voters—about 70,000 to 80,000 of them—include the “wild card” and “unpredictable.”

Each election cycle, scores of political stories trump up the need to woo these undeclareds in order to win New Hampshire. This time around, Republicans Jon Huntsman and Ron Paul in particular have been courting these supposedly independent, contrarian voters. They may be recalling how John McCain shook up the 2000 GOP presidential primary with an upset win in New Hampshire, in part thanks to big support from independents.

The problem is, New Hampshire’s undeclareds are far less unpredictable and malleable than they’re made out to be. Indeed, that image of tens of thousands of voters hemming and hawing until the last minute before casting their presidential primary ballot is a myth, says Andy Smith, director of the University of New Hampshire’s Survey Center. Smith oversees numerous polls gauging the political moods in his state, and based on the data he’s collected over the years, he disputes the notion that New Hampshire’s legions of undeclared voters are likely to tip a presidential primary in one specific direction. “I hear it from reporters all the time,” he says. “They’re saying, ‘How about those independents?’ But they’re really not a bloc of voters.”

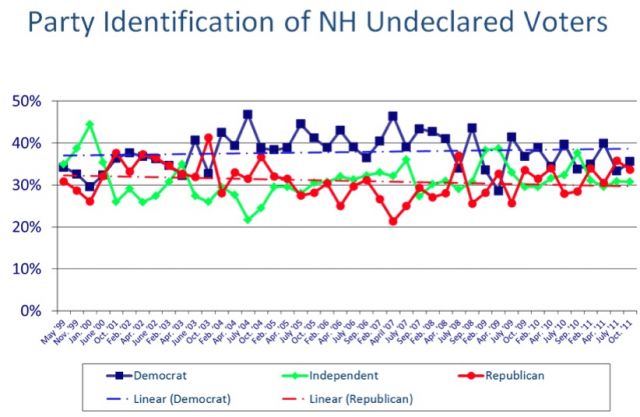

In reality, New Hampshire’s undeclared voters break down fairly evenly along party lines—with the actual chunk of truly independent voters turning out to be much smaller. According to a decade’s worth of UNH polling data, Smith says roughly 40 percent of the group are in fact Democrats: “They act like Democrats and they vote for Democrats.” Another 30 percent are Republicans. The remaining 30 percent, he affirms, are independent voters whose “political attitudes don’t consistently line up.”

Dante Scala, a political scientist at UNH, agrees with Smith’s debunking of the myth. “Most undeclared voters actually lean one partisan direction or another,” he wrote in an email. “Pure independents [are] a minority of undeclareds, e.g., the so-called ‘McBama’ voters of 2008 who were supposedly choosing between Obama and McCain in the primaries.”

Smith’s polling data also shows that undeclared voters have grown more Democratic in the past decade. In 2000, 37 percent of undeclareds identified with Democrats, and 32 percent identified with the GOP. He adds that these voters aren’t as crucial as candidates and reporters make them out to be, because they tend to be less zealous. He describes them more as “apolitical”; they don’t vote as often in elections as New Hampshire citizens affiliated with a political party.

Andy Smith, University of New Hampshire

Andy Smith, University of New Hampshire

Mike Dennehy, a Republican political strategist in New Hampshire who worked on McCain’s 2000 campaign, says he generally agrees with Smith’s take that declarations about the importance of McBama-style undeclared voters are misleading. But Dennehy says undeclared Republicans aren’t exactly party loyalists, either. He describes them as hard-right on fiscal issues and mostly conservative on social issues but as having something of an independent streak that endears them to outsider candidates. “They are looking for a different kind of candidate,” he says. “A John McCain in 2000.”

Dennehy speculates that there could be a surge in turnout among undeclared voters in Tuesday’s primary. That’s not because undeclared Democrats will decide to vote Republican, he says, but instead because the field of Republican candidates is so large. In 2000, for example, undeclareds had only two candidates, McCain and George W. Bush, to choose from in the GOP primary.

A surge in turnout among undeclareds won’t benefit any single candidate, Dennehy adds. The GOP field is crowded and many of the candidates are appealing to voters of all stripes—self-identified GOPers, undeclared Republicans, and true independents. In Huntsman’s case, he’s openly courting Democrats as well as Republicans. A WBUR poll from November found that 16 percent of undeclared voters who identified with no party backed Paul and 13 percent backed Huntsman, while more than 60 percent hadn’t picked a candidate. “You’ve got Mitt Romney who’s appealing to independent voters, Ron Paul who’s doing very well with independent voters, Jon Huntsman who’s doing very well with them,” he says. “I think they’re going to split very evenly between those three.”

In Dennehy’s view, that’s especially bad news for the moderate Huntsman, who has bet all his chips on a strong showing in New Hampshire. He’s unlikely to win over dyed-in-the-wool Republican voters (who will be inclined to vote for Romney) and therefore needs big majorities among undeclared Republicans and true independents.

But no candidate is going to win in New Hampshire next month solely on the support of undeclared voters of any stripe, Smith says. Even in 2000, when the Bush campaign blamed its loss on undeclareds, McCain still won among traditional Republicans, albeit by 2 percentage points. In the end, Huntsman, Romney, Paul, and the rest of the candidates have to win in New Hampshire the old-fashioned way, Smith says. “You gotta win among your own party’s voters.”