A lot of photographers covering war pay lip service to the idea of making a difference with their photos or bearing witness or some noble sounding line of horseshit. Sure, for some of them it’s true; they really believe. Yet most are just adrenaline junkies. Even if they go in with lofty ambitions, they come out addicted. It’s rare to run across a journalist like Tim Hetherington, the British photographer who was killed in Misrata, Libya, in April 2011 while covering the revolution that overthrew Moammar Qaddafi. He was an exceptionally talented photographer with true aspirations of not just making a difference with his photos, but trying to understand the people he was photographing and the reason he was there.

Less a biography than an intimate tribute, the new film Which Way Is the Front Line From Here addresses head-on the reasons Hetherington went to shoot war and kept going back. Directed by Sebastian Junger, with whom Hetherington made the Oscar-nominated documentary Restrepo, it not only offers personal insights into who Hetherington was but addresses the larger issues of covering war, the issues that drove Hetherington.

For anyone who has ever entertained the idea of going into a war zone with a camera, or known someone who has, “Why?” is a hard question to answer truthfully. For Hetherington, the answer evolved from a need to find out who viciously blinded the children he photographed at a school for the blind in Liberia, to addressing how young men see themselves in war, to telling the story of combat as the ultimate bonding experience.

That’s not to say Hetherington was immune to the rush. Before going to Libya, he talked about giving up war photography. But something drew him back—the story, the adrenaline, the camaraderie, the addiction. Photojournalist Andre Liohn, who was also in Libya with Hetherington, says, “In war you can lose a lot of things. One of those things you lose can be the original connection that took you there. They”—the group of photographers that Hetherington was with—”were actually trying to get in front of the rebels.”

Hetherington didn’t hopscotch the globe from one hot spot to the next. He really only covered three conflicts: the Liberian civil war, Afghanistan, and the Libyan revolution. He stayed in Africa for nearly a decade, remaining in Liberia well after the war wound down, documenting and helping with the recovery. In Afghanistan, he covered a remote American outpost in the Korengal Valley, staying with troops for months on end, amassing the photos and footage that became Restrepo. And Libya seemed to have drawn him in against his own wishes. And yet he went.

Like the best conflict photographers, Hetherington was smart about what he shot and what he wanted to show in his photos. Images of fighting, the actual bang-bang, carry less weight than the quiet moments of war, the before and after, the crushing impact. Junger talks about how Hetherington chewed on the idea of a feedback loop of war imagery: Soldiers imitate the men in photos they’ve seen and how he was stuck in that loop, creating images of soldiers that will surely be seen and imitated. Hetherington worked hard to create other kinds of images.

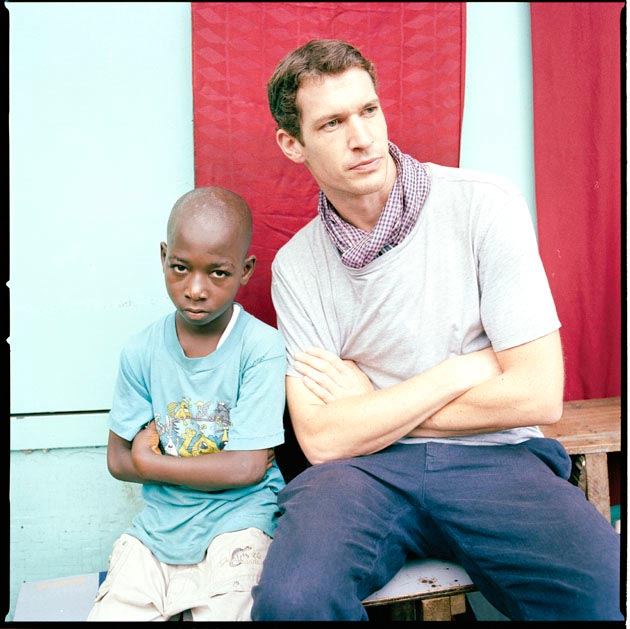

In addition to the digital images and video he shot, Hetherington regularly shot film on a bulky medium-format camera. This forced him to slow down and think about the photos rather just reacting. These subtle, poignant photos get under the skin of war. He shot portraits of children in war zones, of rebels saying goodbye to their loved ones. He photographed soldiers as they slept, capturing their fear and exhaustion and pain. Sure, Hetherington ran with soldiers and pushed his way to the front lines, but Which Way Is the Front Line From Here shows him working to make sense of what’s happening around him.

There’s a lot to unpack in this relatively short film. It is inspiring and cautionary. It’s thoughtful yet somewhat complicated. It’s titillating and ultimately sad. Hetherington’s frequent use of video makes the documentary much more than a roundup of still photographs and friends rehashing war stories and. The first-person point of view lets you see what Hetherington saw, right up to the day he died.

Watching Hetherington running with Liberian rebels, dodging gunfire, breathlessly making pictures and covering his ass appeals on the same visceral level as any action movie. It gets your heart racing. It stirred the palatable desire to cover war that I used to flirt with. The titillation of the gorgeous, moving combat photography and jerky, heated video footage under fire is tempered by the ultimate outcome of the movie. You see the explosion that killed Hetherington and the impact his death had not just on his family and friends but the broader community of journalists. In losing Tim, we didn’t just lose another great photojournalist, we lost one of the few truly committed photographers, whose work behind the camera and away from it actually made some kind of difference.

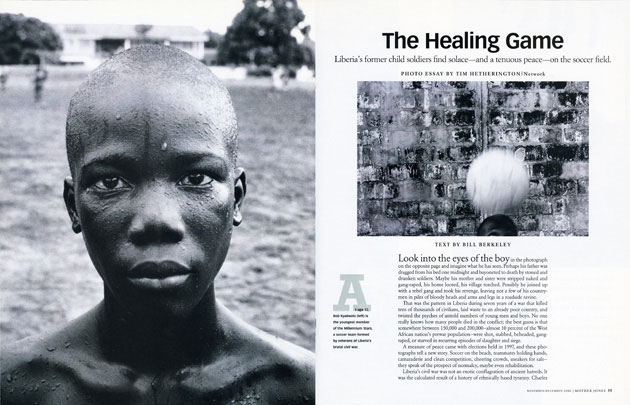

Hetherington’s photographs appeared in Mother Jones in 2000, 2004 and again in 2008.

Which Way Is the Front Line From Here: The Life and Times of Tim Hetherington, directed by Sebastian Junger, airs on HBO Thursday, April 18.