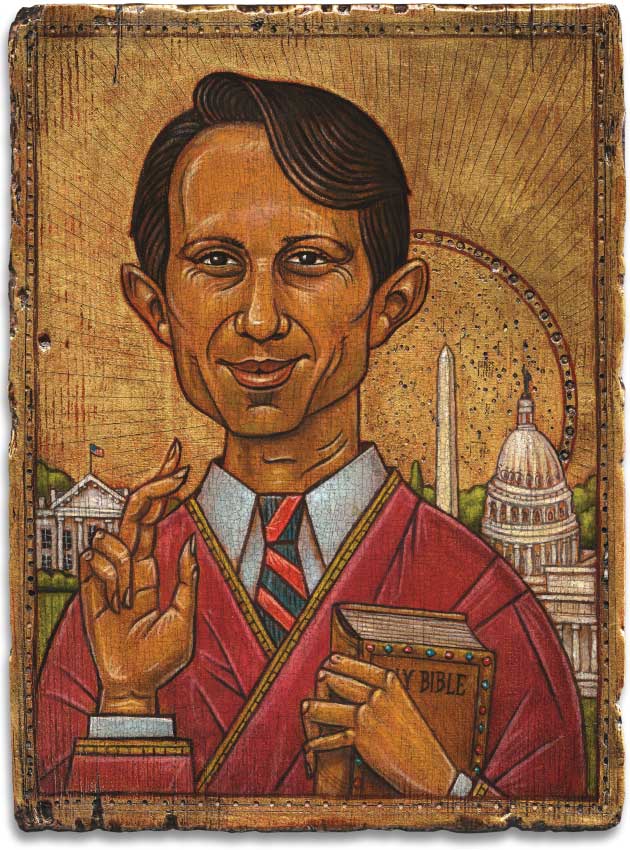

BOBBY JINDAL has never been one to wait. And so in November 2012, just one week after Barack Obama was reelected in a race the conservative establishment had long refused to believe it might lose, the 41-year-old governor of Louisiana stuck a knife in Mitt Romney’s back.

The party’s old guard was reeling and Jindal seemed poised to take advantage and confirm that he was a contender to lead the party in 2016. In winning a second gubernatorial term one year earlier, Jindal had crushed his top Democratic challenger by nearly 50 points, helping Republicans take control of the state Senate for the first time since Reconstruction. As Romney exited the national stage, Jindal was locking down the chairmanship of the Republican Governors Association (RGA), a perch that is generally considered a steppingstone to bigger things because of its access to a national network of conservative donors. And in his personal story and ethnic heritage, he offered a walking counterpoint to his party’s demographic stagnation.

Jindal’s message was blunt: It was time for Republicans to “stop being the stupid party.” Stop saying dumb things to reporters or constituents wielding cameras, or even at $50,000-a-plate fundraisers. Stop offering “dumbed-down” conservatism. Stop “reducing everything to mindless slogans.” Stop defending big corporations. He tried the theme again two months later, at a Republican National Committee meeting: “It’s time for a new Republican Party that talks like adults.”

It was supposed to be a spotlight-seizing moment. But his rivals saw a chance to call out a weakness. As New Jersey Gov. Chris Christie put it, “I’m not going to be one of these people who goes around and calls our party stupid.”

Then Jindal’s signature second-term proposal, a dramatic overhaul of state taxes backed by leading conservative activists like Grover Norquist, died spectacularly at the hands of the Legislature. And this past November, Virginia Republicans blamed missteps by Jindal’s RGA for Ken Cuccinelli’s failure to seize the governorship. Adding insult to injury, it was time for Jindal to cede the chairmanship to Christie, who had just been reelected in a landslide. “Bobby Jindal’s presidential campaign is over,” one Virginia GOPer fumed.

Even as the Republican Party’s great mentioners have largely moved on without him, Jindal is continuing on as if this is all part of the plan, quietly laying the groundwork for that long-expected White House run by staffing up his Washington-based nonprofit, America Next, and making regular trips outside of Louisiana to gather chits and speak at state party chicken dinners. It’s “very obvious to everybody who has been paying attention” that Jindal is running, his home state Republican senator, David Vitter, said in December. Can a man whose political career has been built on a series of reinventions remake himself one more time?

Jindal was elected governor of Louisiana seven years ago at the age of 36 and anointed, almost immediately, as the Republican Party’s golden boy. He seemed assured of a spot in every presidential discussion for as long as he wished; as a former Rhodes scholar and congressman and a conservative of color, he had just the kind of brain—and face—that the bigwigs wanted representing their party in the age of Obama.

“The question is not whether he’ll be president, but when he’ll be president,” gushed Steve Schmidt, John McCain’s presidential campaign manager, in 2008. “The next Ronald Reagan,” pronounced Rush Limbaugh. Such praise was common: Few Republicans could match his résumé.

But midway through his second and final term in Baton Rouge, Jindal’s future looks far less bright. Among conservative kingmakers and talk radio hosts, he’s been eclipsed by a succession of shinier objects: Christie, Marco Rubio, Ted Cruz, Rand Paul.

The Republicans’ recent history is littered with politicians who have been promoted with the hopes of countering the appeal of the nation’s first black president. “When you see a candidate who has had success as an outside candidate, you look for the person on your side who most directly replicates them,” says Schmidt. Michael Steele was elected to chair the party after a failed Senate run and one term as lieutenant governor of Maryland. Political novices Herman Cain and Ben Carson both earned presidential buzz, and no discussion of the appeal of Rubio or Cruz, both Senate newcomers, goes far without a nod to their Latino heritage.

Jindal has a better CV than anyone else in that crop, and one that would be the envy of most of his rumored 2016 rivals. But as governor, he has failed to match that résumé with the policy achievements you’d expect in a national candidate. As his last day in office draws closer, it’s unclear just who remains passionate about Jindal trading up to the White House, or if he ever had the political acumen it takes to win a presidential nomination.

In Louisiana, his approval ratings have at times dropped below 40 percent, weighed down by frustration that he has spent too much time looking for his next job and not enough on the one he has now. In November, the congressional candidate Jindal selected for a special election he’d engineered lost by 20 points to a political novice running on a promise to, of all things, expand government-run health care.

“He’s young, he’s smart, he’s a reformer, but he’s very ambitious,” says Buddy Roemer, a former governor whose son Chas is a Jindal ally who chairs Louisiana’s board of education. “It’s the ‘ambitious’ that’s gotten in the way of the other things.” Specifically, it has kept him away from the governor’s office: The Associated Press calculated that he now spends one out of every five days out of state.

Yet Jindal’s relentless drive may also be why Republicans are wary of counting him out. Clancy DuBos, a longtime columnist for the Gambit, a New Orleans weekly, recalls an old Louisiana lobbyist’s characterization of the governor: “‘If you cut that boy open from stem to stern, won’t nothing bleed out but ambition’—that’s what Bobby’s all about.”

Few things endear a politician to his base like a good conversion narrative. Jindal has an uncannily vivid one, developed in his memoir, in speeches, and in a series of little-noted religious essays published in the 1990s. The effect is a sort of conservative counterpoint to Barack Obama’s coming-of-age story—with none of the drug use and only some of the disaffection.

It’s tough to distinguish Jindal’s faith journey from his political one, mostly because he himself doesn’t. His parents came to Baton Rouge from Punjab when his mother was three months pregnant. Born Piyush Jindal, by kindergarten he had asked to be called Bobby, after hearing the name on Brady Bunch reruns. The family raised him in their Hindu faith, worshipping weekly and attending services at neighbors’ homes. Then, in middle school, his best friend, Kent, told him he was going to hell, setting off years of spiritual questioning. Jindal read the Bible by flashlight in his closet, an experience he has compared to that of early Christians who practiced under threat of persecution; wanting to weigh his options, he asked his parents for a copy of the Bhagavad Gita.

But Jindal found Hinduism lacking in absolutes, and after watching a grainy film depicting the crucifixion in a back room at Kent’s evangelical church, Jindal gave himself up to Christ. For a year, he kept his conversion secret from his parents, sneaking off to worship behind their backs. When he finally came out as a high school senior, he’d already been admitted to Brown University; worried that his family would disown him and refuse to cover the tuition, he’d lined up a job and a scholarship to Louisiana State as backup. His parents relented, albeit reluctantly; they refused to attend his baptism and spent the next decade praying for him to come back to their faith.

Providence, Rhode Island, seemed to Jindal an unfamiliar and often hostile world. As a strong conservative—his high school sweetheart had convinced him of the evils of abortion the night of their first date—he felt like a curiosity on a campus where classmates spelled “womyn” with a “y” and an orientation week exercise asked straight students to pretend they were gay.

But then Jindal found his niche. He threw himself into his pre-med classes and joined the Brown Christian Fellowship and Campus Crusade for Christ, a tight-knit group of committed believers.

Though his childhood explorations of Christianity were alongside charismatic Protestants, Jindal now found himself drawn to the structure and absolutism of Catholicism, taking on Latin and poring over the complete volumes of Thomas Aquinas. After a campus priest plucked him from the pews to light an altar candle, Jindal decided to be confirmed in the church.

It was not to be a private belief: Jindal felt a moral imperative to evangelize, and classmates recall he was an active salesman for the Lord. He had embraced a traditionalist vision of Catholicism out of step with the modern church, one in which evil was something to be confronted not just spiritually, but physically. And it wasn’t long until he saw an opportunity to put his faith into action: In a 1994 essay for the New Oxford Review, one of a dozen pieces he would write for small Catholic journals about his conversion, he described participating in an exorcism of a classmate he called “Susan.” Jindal and Susan had shared a platonic friendship, but their relationship had frayed in recent months. Susan had begun having mysterious visions. She was also being treated for skin cancer. Visitors to her apartment reported a faint odor of sulfur.

The church hierarchy sanctions exorcisms only with the blessing of a bishop. (A 2000 estimate put the global figure at fewer than 600 a year.) But Jindal didn’t ask a priest or any other church official for help, he explained, out of fear: What would it mean for his faith if he discovered the church was powerless to help his friend?

The conflict came to a head at a hurried evening intervention. “Kneeling on the ground, my friends were chanting, ‘Satan, I command you to leave this woman,'” Jindal recalled. “Others exhorted all ‘demons to leave in the name of Christ.'” Finally, another student showed up with a crucifix and cast the spirit away.

Jindal and his friends never fully came to terms with what had happened to Susan. Maybe she had invited “pagan influences” into her life by living with a Hmong roommate. Or perhaps it was an offering her mother once made at a temple in Southeast Asia. Or maybe demons had nothing to do with her problems.

“We were college students who were playing with atomic material and really didn’t know what we were doing,” recalls Michael Tso, a fellow member of the Brown Christian Fellowship. And it wasn’t their only confrontation with evil; another acquaintance claimed that a demon had slashed her arms. “It was probably the most intense experience that I’ve ever experienced,” Tso says.

There was an upshot to the episode: Susan saw the light. Three years after he first wrote about the night with the crucifix, Jindal revisited his demons in an essay for This Rock, a conservative Catholic journal. Though Susan was now “Agnes,” he left no doubt they were the same person. Jindal, by then a political rock star, painstakingly filled in details of their relationship, from a chance meeting on the way to Mass on his first Sunday in Providence to the mysteries—and men—that came between them. “Agnes’ confirmation was the most incredible and intense day of my life, second only to my own baptism,” he wrote. The dance with the devil brought them closer than they’d ever been, and after she’d come into the light they emerged as a committed couple, traveling to Vienna and the south of France, and making a pilgrimage to Rome. “Few outsiders will ever understand what happened between us,” he wrote. “Agnes was my hero, and I suppose I was hers.”

Demonic confrontations aside, Jindal thrived at Brown, earning top marks in his pre-med track and exploring health care policy issues in his thesis and as a summer intern for Rep. Jim McCrery (R-La.). After graduating early at age 21, he put off his dreams of becoming a neurosurgeon, turning down offers from both Yale’s and Harvard’s medical schools to take a Rhodes scholarship.

Bill Clinton, elected president while Jindal was at Oxford, had launched his Arkansas political career 25 years before on the basis of little more than having received the same honor. “Being a Rhodes scholar, especially from a small Southern state, marked you with tremendous potential,” says fellow scholar Noah Feldman, now a Harvard Law School professor and Bloomberg columnist. In 1993, Clinton returned to the place where, as the New York Times‘ Maureen Dowd acidly put it, “he didn’t inhale, didn’t get drafted and didn’t get a degree.” Of the American students he met that day, Jindal was the only one who hadn’t voted for him.

Jindal’s contemporaries at Oxford—among them future Los Angeles Mayor Eric Garcetti and Sen. Cory Booker (D-N.J.)—remember him as outspoken in his conservatism, inviting friends over to his apartment to make pizza and talk about abortion. He was sufficiently impressed with himself, one classmate recalls, that fellow students shamed him into dropping coins in a jar every time he mentioned he was a Rhodes scholar. But for all his passion, Jindal projected more wonkiness than political magnetism: “Cory Booker was the most charismatic person anyone had ever met,” Feldman says. “Bobby cared about policy and went to McKinsey.”

Indeed, Jindal left Oxford with yet another thesis on health care—and a new career: Rather than work in hospitals and help thousands of people, he told himself he’d work on health care systems and help millions. After 16 months as a McKinsey consultant, he called McCrery to ask for help getting a job, and in 1996 was appointed Louisiana secretary of health and hospitals.

Someone older might have considered the post a career-capping achievement, but the 25-year-old was already thinking bigger. “The Republican Party certainly has to do a lot of soul-searching,” he told C-SPAN following Clinton’s reelection, exhibiting little trace of his now prominent Southern drawl. It wasn’t long before he concluded that what the Republican Party really needed was him.

Through a mix of merit and good luck, the promotions came fast. Jindal landed a gig running a federal commission on Medicare, became president of the state university system, and then was named an undersecretary of health and human services by George W. Bush. In 2003, he ran for governor and lost to Democrat Kathleen Blanco by 4 points in a race defined by identity politics. Jindal faced whispers suggesting he was a Muslim, while Blanco played up her Cajun roots by adding her maiden name, Babineaux, to campaign signs. A Blanco ad hammered cuts he made while heading the department of health and hospitals, leading the front-running Jindal to falter down the stretch.

But the loss was only a speed bump. One year later, after his future rival David Vitter moved up to the Senate, Jindal filled his solidly red congressional seat. And in 2007, with Blanco having opted not to stand for reelection after a widely criticized response to Hurricane Katrina, Jindal took the stage at a Baton Rouge Holiday Inn, thanked his wife, Supriya, and their three children, and claimed the governor’s office.

Last year, when Jindal railed about the “stupid party,” he may well have been trying to highlight his own brainy reputation. It’s a brand he has carefully cultivated: Profiles of the new governor tended to emphasize his wonky smarts, characteristic of an administration that promised to be heavy on policy and light on flair. That, the thinking went, was exactly what Louisiana needed. Jindal was alternatively “slight, unassuming”; an “earnest dork”; “like a college intern”; “a regular Alex P. Keaton”; and the crown jewel of the bunch, a “boyish politician” so above it all that he “rarely bothers to eat or urinate when traveling.”

And when Barack Obama was elected president, Jindal was no longer just a wonk—he was a savior. National outlets had covered his election in much the same way as Obama’s initial Senate victory, with dreamy musings about how Jindal’s prominence might improve America’s image and with reporters traveling to Punjab to file incredulous reports of cousins who weren’t sure where Louisiana was. Conservative flagships like National Review and the Weekly Standard fawned over his combination of social conservatism and pointy-headed policy prescriptions. After enduring eight years of Bush-bashing, conservatives envied Jindal’s combination of brains and self-made success.

As governor, Jindal had an opportunity to put his big ideas into action. But his bold prescriptions look a lot like the same ideas Republicans have been pushing for decades—perhaps not surprising for a man who started out in an industry built around telling corporate leaders what they already know.

The centerpiece of his agenda was education. When he took office, Louisiana had some of the nation’s highest dropout rates and lowest literacy scores, and Katrina had battered New Orleans’ school system. Like another Southern governor, Jeb Bush, he built a reputation as an education reformer from the GOP mainstream—charter schools, teacher merit pay, and a voucher program to pay private-school tuition. But Jindal’s agenda also had a strong Christian flavor. In 2008, he signed the Louisiana Science Education Act, which allows public schools to challenge the science of evolution. Jindal framed it as a matter of giving local districts more control, but the effect was obvious: Thousands of high school students, especially in the state’s Baptist and evangelical north, could be exposed to creationist teaching materials.*

Some think Jindal was simply playing politics, rewarding a religious demographic that was instrumental to his rise. “He’s smart—he was nearly gonna go to Harvard Medical School. I can’t believe that he believes in creationism,” says 20-year-old Zack Kopplin, who, as a high school student, persuaded 75 Nobel laureates to sign a letter opposing the legislation. But Jindal’s own statements suggest otherwise: As far back as 1995, fresh off his final semester at Oxford, Jindal wrote that there was “much controversy over the fossil evidence for evolution.”

Jindal’s voucher program has so far funneled at least $4 million to religious institutions, many with strict discriminatory policies. In the state’s northeastern corner, Claiborne Christian Academy students believed to be pregnant can be suspended and expelled upon confirmation. (An abortion warrants expulsion, too.)

Other voucher-funded schools in the region subject gay students to the equivalent of Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell. At Northlake Christian School in Covington, students can be refused admission if they or their family promote the “homosexual lifestyle.” Northeast Baptist School in West Monroe states that “students that profess a sexual orientation contrary to God’s Word will not be accepted and may be un-enrolled…upon discovery.”

“I guess they would confess it, and they would talk about it to the kids, and I would ask about it,” says Anita Watson, Northeast Baptist’s principal, when I call to ask how the school would find out about gay students. “To be honest, it hasn’t ever really come up because the teenagers that, I don’t know, that are leaning in that direction, they would probably choose not to come here.”

While aspects of Jindal’s education policies evoked Bush-era compassionate conservatism, in most areas he has embraced brute austerity. In the name of cutting waste—overspending has historically been a vehicle for corruption in Louisiana—Jindal has sought to slash the services on which residents of the nation’s third-poorest state have depended. He moved to cut the retirement benefits of some state employees by as much as 50 percent, while blocking even incremental increases in levies like the cigarette tax. State funding for higher education has been cut by 80 percent, with Jindal turning down federal stimulus funds that could have filled some of that gap. And last spring he vetoed $4 million to help relieve a 10-year waiting list for developmentally disabled Louisianans seeking in-home care.

Jindal touts his record as the first Louisiana governor in recent history not to raise net taxes. Instead, his approach has been to shift more of the tax burden onto the state’s poorest residents, while giving high-earners a break: In 2013, he proposed increasing sales taxes so the state could eliminate all income and corporate taxes. (The plan died amid bipartisan rebellion.) And like 24 other Republican governors across the country, he turned down funding to expand Medicaid under the Affordable Care Act, denying coverage to 214,000 low-income Louisianans.

Jindal’s zeal to keep spending low and protect his reputation as a budget hawk has undercut other initiatives. He brought on environmentalists to help write his 2012 plan to shore up the coastline, but has so far fruitlessly insisted Washington, not Baton Rouge, foot the bill. When the state’s independent flood control board sought funding for the plan by suing 100 oil and gas companies for elevating flood risks through the construction of pipelines and canals, Jindal—who has received more than $1 million in contributions from the industry—asked the courts to throw the case out, and when that failed, replaced three of the board’s members. And even though Jindal had called outdated ethics rules the No. 1 obstacle to economic investment, and had pushed through an overhaul, his budget dramatically slashed the number of employees keeping watch; an analysis by the Center for Public Integrity gave Jindal’s administration a D+ for enforcement of corruption laws.

Jindal, who set a strict contribution limit on his own wedding registry when he served in the state cabinet, has himself avoided any crippling scandals. But the New Orleans Times-Picayune has found that almost every appointment he has made to a state board had been preceded by a hefty donation to his campaign.

Steve Schmidt, who once called a Jindal presidency inevitable, doesn’t go so far today. But he’s still bullish. “If you look at the long-term group of men—and it is men—who are in his peer group and are most speculated about, Marco Rubio, Ted Cruz, flavors of the month…I would still say Jindal has the best chance of being elected president.”

Even with some of the luster worn off, Schmidt reasons that after eight years of Obama, Republican primary voters may think twice before picking a first-term senator like Paul, Cruz, or Rubio. And they might hesitate to back a governor who has yet to earn the trust of social conservatives, like Christie. Maybe they’ll gravitate toward someone fluent in the language of both the religious right and the Heritage Foundation, someone who built his political career outside of Washington. There’s still that résumé, in other words.

But presidential politics demands more than a promising career path—it requires success in real-world political wrangling, and on that front Jindal has not been so strong. His constant travel has eroded his stature at home—one state appointee who supports Jindal calls him an “absentee landlord”—and made it harder for him to amass the kind of accomplishment or high approval levels that national campaigns are made of.

“They respect him. They like him,” Roemer says of Jindal’s relationship with Louisiana Republicans. “But they think the problems here are what he was elected to solve. And he went AWOL.”

An investigation into Jindal’s dealings with lawmakers by the Lens, a New Orleans news site, found no fewer than a dozen Republican representatives willing to knock him on the record for his hands-off style. As likable as some legislators might find the governor, Lens reporters were unable to identify a single one who considered him a friend.

Meanwhile, Jindal’s nemesis, fellow Rhodes scholar David Vitter, has been making things increasingly difficult for him. In 2007, many predicted that Vitter would be crippled after his number turned up in a prostitution ring’s phone records, surfacing rumors that he had a predilection for diapered dalliances. While the scandal limited his avenues to advance in Washington, it prompted him to shore up relationships within Louisiana’s GOP, ensuring he remained a powerful force in the state’s politics. Vitter, who never endorsed Jindal’s tax reform plan, is closely associated with a group of Baton Rouge lawmakers who have criticized the governor’s budgets from the right. Last fall, he embarrassed the Jindal administration by demanding a full state investigation after a broken EBT machine at a northern Louisiana Walmart improperly processed food stamp payments, allowing shoppers to pick the store clean. Vitter’s move propped up an ugly story for a governor who has railed against a “culture of dependency.”

Weakened at home, with his final term half over and the Republican presidential primary field taking shape, Jindal risks becoming yesterday’s news. “I think he is, and I think he actually has been for quite some time,” says Elliott Stonecipher, a conservative pollster and former Roemer aide in Louisiana. “The RGA job was maybe his last gasp at putting something back together, and it didn’t work.”

Jindal’s recent swoon suggests just how much of his earlier success might have been a matter, as much as anything, of lucky timing: He came of age as a Republican in an era when Republicans were newly ascendant in Louisiana politics (Bill Clinton became the last Democratic presidential candidate to carry the state in 1996) and climbed the ranks of the state bureaucracy in part because he was a big fish in a small pond. Jindal would have been a talent anywhere, but Louisiana wasn’t exactly overflowing with Oxford-educated Republicans with immigrant tales. And in Hurricane Katrina, he was handed a powerful electoral tool, not just because it made Blanco unelectable, but also because it ended with tens of thousands of Democratic New Orleanians living in Texas. Eventually, it was inevitable that Republican grandees would be attracted to someone who could help suggest the party was evolving beyond its overwhelmingly white voter base.

“He’s a political alchemist—he weaves webs out of what he claims is gold,” says DuBos, the Gambit columnist. “Was he ever really the GOP golden boy, or was that just him spinning?”

Maybe the genius of Bobby Jindal is that he made us think he was one.

*Correction: The original version of this article, which ran in our March/April 2014 print edition, incorrectly suggested that the Louisiana Science Education Act had allowed public school students to be taught that the Loch Ness monster proved humans and dinosaurs existed together. That incident actually occurred in a private school that received state funding through a voucher program.