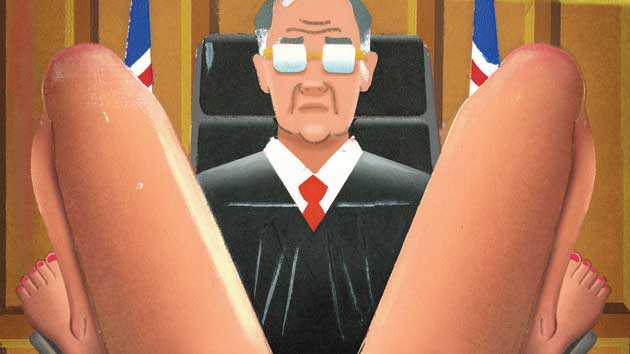

Illustration by Pete Ryan

By January, Kiera had stuffed so many small bills into the envelope hidden in her underwear drawer that it split open. Kiera knew her mother occasionally cased her room, so to be safe, she’d labeled the envelope “soccer camp.”

“It had to be cash,” says Kiera (not her real name). She lets out a nervous laugh. “I couldn’t write a check and write ‘abortion’ on the memo line.”

Kiera, who lives in the Florida panhandle, is thoughtful, sarcastic, and whip-smart. It’s easy to forget that she’s only 18. But in December—when she was staring down a positive pregnancy test, thinking, shit—she was only 17. Florida is one of 37 states where a minor can’t have an abortion unless at least one of her parents knows about it. Twenty-one of those states (though not Florida) require at least one parent to grant permission.

Kiera’s parents are divorced, and her father lives on the other side of the country. Her mother, Kiera says, is “unstable,” unpredictable, and sometimes violent. Once, she kicked Kiera out of the house for forgetting to tell her about a sleepover, and it took a whole weekend for her to cool down. Kiera was sure that if she told her mom, who volunteered for an anti-abortion group, that she wanted to end her pregnancy, she’d be out of the house for good.

But when Kiera confided in a school counselor, she learned about another option: She could ask a judge for permission to have an abortion. Her panic melted away. “I thought, ‘This will save me,'” she recalls. She started socking away every dollar she could get her hands on—lunch money, tips from her waitressing job. And she started calling courthouses.

EACH YEAR, HUNDREDS of girls in Florida petition judges for permission to have abortions; the nationwide number is likely in the thousands. But those statistics only include the girls who make it to court. Poorly trained court staff, anti-abortion judges, and a spate of increasingly restrictive laws have made it harder than ever for minors to exercise their legal rights.

Abortion foes have pushed for new restrictions because they believe the process, which is known as judicial bypass, is simply a loophole girls use to avoid talking to their parents. “Judges are rubber-stamping these requests,” Ohio Right to Life warned in a press release in 2011, just after John Kasich, the state’s new Republican governor, signed a bill making the bypass process stricter.

But a review of more than 40 cases, along with interviews with minors and their attorneys, reveals that in much of the country, obtaining a judge’s approval to get an abortion is a mammoth struggle.

“‘Daunting’ doesn’t begin to cover it,” says Jennifer Dalven, who runs the reproductive rights arm of the American Civil Liberties Union. “Imagine it: You’re 17 years old. You’re already struggling with this unplanned pregnancy. You may be afraid of your parents. And now you’re told, ‘Go to court’?”

Susan Hays, a Texas attorney who represents minors through a group called Jane’s Due Process, says about a third of the girls she works with don’t have the option of asking their parents for permission—they’re undocumented immigrants whose parents are not in the country, orphans, or what Hays calls “de facto orphans”: “Mom’s dead, Dad’s in prison, they never liked me much anyway.” She once represented a minor whose parents ran a meth ring: “She had split because she had the distinct impression they were going to start pimping her out.” Legal guardians may grant permission for an abortion in most states. But this is no help to girls who live with family members who never established guardianship.

It isn’t supposed to be this way. In 1979, the Supreme Court ruled that a girl’s parents can’t exercise an absolute veto over her right to an abortion: States requiring parental notification or consent had to provide an escape hatch. The court did not mandate what form this escape hatch should take. Maine, for example, allows a physician to decide whether the minor is competent enough to make her own decision. But that’s not good enough for anti-abortion activists. Led by Americans United for Life, the legislative wing of the pro-life movement, they’ve advanced laws to put the decision in the hands of judges instead.

The process sounds simple: Go to a courthouse, file a form, and get a private hearing within a day or so. If the judge—who usually holds the hearing in his or her chambers—denies the petition, a minor has a right to a speedy appeal. A pregnant teen, according to standards defined by the Supreme Court, must show either that she is mature enough to have an abortion without her parents’ involvement or that an abortion is in her best interest. “The way most laws are written, if you follow the statute, Jane Doe wins almost every time,” Hays says. But in practice, girls are at the mercy of whichever judge they happen to draw, says Anne Dellinger, a retired University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill professor who has studied the bypass system. “If a girl wanders into the wrong [court], she doesn’t have a chance,” Dellinger says. With few checks on the system, Hays adds, judges are free to impose their beliefs on the girls who appear before them: “It’s the law of bullies.”

KIERA FINALLY APPEARED before a judge, a man nearing retirement age, when she was about 10 weeks along. Playing phone tag with the court had taken nearly three weeks.

Her school counselor said financial assistance from the clinic covered the gap between what she had squirreled away in the envelope and the cost of the abortion, but Kiera suspected her counselor paid the difference herself. She didn’t care. By now, she had begun gaining weight and was sweating nonstop.

From the outset of her hearing, which Kiera weathered without a lawyer, the judge made his feelings about abortion clear. “I said, ‘I’m an A and B student,'” Kiera recalls. “I tried to use my SAT words.” The judge was not interested. He grilled her on whether she had contemplated her decision in church, or thought about how she might regret an abortion when she looked at her children in the future. He was upset to learn Kiera wasn’t dating the father.

When they discussed her family, the judge began pleading. “He said, ‘I’m sure your mother would understand,'” Kiera recalls. “He was kind of panicking—I felt like he was saying, ‘Well, have you tried having a better mother? Have you tried religion?'” The judge adjourned the hearing without a ruling. It wasn’t until two days later, after Kiera had already canceled her appointment at the clinic, that she got a call to come back to court. He’d granted her petition.

Kiera’s case ended as she’d hoped. But court records show many girls are not so lucky. In the 40 cases I reviewed, judges denied minors’ petitions for arbitrary, absurd, or personal reasons—such as a minor’s failure to discuss her decision with a priest. (Although the initial hearings are private, summaries and partial transcripts became public when the minors appealed.)

In 2008, Florida Judge Raul Palomino Jr. urged a 17-year-old to think of how distressed her Catholic parents would be if they discovered her secret abortion. In a 2006 Florida case, a girl testified she wasn’t financially or emotionally equipped to raise a child—a claim, the judge ruled, that proved she wasn’t mature enough to choose abortion. Three judges denied petitions because becoming pregnant by accident indicated a young woman was too immature to choose abortion.

The records I reviewed show that if a judge doesn’t want to grant a petition, she will find a reason to deny it. One 17-year-old in Alabama tried to satisfy the state’s requirement that minors be well informed by asking six people—a woman who’d had an abortion, a family friend, two nurses, and staffers at Planned Parenthood and the local health department—about the procedure. In court, she described the procedure in detail, naming the surgical instruments used. When the judge asked the girl—a straight-A student bound for college on two scholarships—if she felt emotionally ready to have an abortion, she replied, “I am. I’ve been strong-minded about all of this.”

The judge then denied her petition because she hadn’t spoken to the doctor who would perform the procedure. (The girl said the doctor refused to talk to her; clinics often limit contact with minors before their bypass hearing.)

“I’m a mother,” said the judge, who is not named in the court documents. “These people are interested in one thing, it appears to me, and that is getting this young lady’s money…This is a beautiful young girl with a bright future, and she does not need to have a butcher get ahold of her.” A divided appeals court upheld the judge’s denial.

In a 2013 case that made headlines, a Nebraska court decided a 16-year-old in foster care was not mature—in part because she was “not self-sufficient.” The minor had raised her siblings when her parents weren’t around. The Nebraska Supreme Court upheld the lower court’s decision.

In another case, an appeals court described the testimony of a young woman who petitioned an Alabama judge in 2000:

“Her father drinks to excess and becomes violent. Recently, she said, he slapped her and told her to ‘get out of the house’ after she had asked him to turn down the volume of the television because she was trying to do her homework…Her father had told her that if she ever came home pregnant he would kill her. She also stated that she did not believe he meant this literally, but that she believed he would whip her. She testified that her mother was also violent and had beaten her older sister until she bled.” The judge denied her petition.

In Alabama and Florida, some judges went so far as to appoint lawyers for girls’ fetuses, even giving them names. “You say that you are aware that God instructed you not to kill your own baby,” one attorney, who represented “Baby Ashley,” thundered at his 17-year-old adversary. “But you want to do it anyway?”

IN SOME WAYS, these girls were lucky to have made it to court at all. They had to get out of school, and in some cases to another town, for the hearing (and the procedure itself). They had to keep the whole process a secret—some attorneys with Hays’ Texas group use Snapchat, a smartphone app that deletes messages after they’ve been viewed. But for many girls, the biggest obstacles are the court employees who act as the gatekeepers of the bypass system. For her 2007 book Girls on the Stand: How Courts Fail Pregnant Minors, Lafayette College law professor Helena Silverstein and a research team called court employees across three states. They found more than half of the courts “proved absolutely or materially ignorant of their responsibilities” under bypass laws. Many court employees, and one judge, told the researchers judicial bypass didn’t exist. Some court staff lectured callers about abortion or referred them to anti-abortion crisis pregnancy centers. Others warned that their judge had a blanket policy of denying petitions.

“We do not do that here,” a staffer told Kiera at the first courthouse she called. When Kiera became upset, the staffer hung up on her. She called the courthouse back and spoke with a different staff member, who was apologetic, but equally clueless.

At the second courthouse Kiera called, no one answered the phone for several days. Finally, she was told, “That’s something you need to ask your mother and father about.” Kiera cajoled the staffer into looking into the court’s bypass procedures. Later that week, the staffer left a message on Kiera’s mom’s answering machine explaining the process. Kiera frantically deleted the message before her mother got home.

None of this is unusual. In March 2012, students at the University of Michigan replicated Silverstein’s study, calling each of Florida’s 67 county courthouses. “Our results…were even worse than we had suspected,” they wrote. “Over two thirds of courts were unable or unwilling to provide callers with the correct or complete information.”

Sometimes, lawyers can counter the system’s failings. In the early 2000s, the ACLU won several cases that sharpened Florida’s legal definition of maturity, resulting in fewer arbitrary rulings. In Illinois, the group is collaborating with the courts to make the process quicker and fairer. In Texas, Jane’s Due Process has had several judges who never approved petitions removed from the rotation of those hearing cases.

But since 2010, many states with new Republican governors—or new GOP majorities in their legislatures—have made the bypass process stricter. Lawmakers in Florida, Kansas, Nebraska, North Dakota, and Ohio have ratcheted up the standard of evidence in bypass hearings. Ohio and Oklahoma restricted the counties where young women can petition. Arizona and Arkansas passed laws forbidding anyone other than lawyers or court staff from helping a girl obtain a bypass.

A new Florida law requiring minors to seek judicial bypass in courts close to their homes is the work of state Sen. Kelli Stargel, an abortion foe who became pregnant at 17, married the father, and had the baby. John, Stargel’s husband, went on to serve in the Florida House, where he helped write Florida’s parental notification law in 2005. He now serves as a circuit judge—and sometimes rules on bypass petitions.

“Some of these children were being taken many, many miles from home,” Kelli Stargel told me. “The child doesn’t need to go out of the umbrella of the parent’s protection. For all we know, the judge will deny the bypass petition, because he determines the parent should become involved.”

In April, Alabama passed a law formally recognizing the right of judges to appoint lawyers to represent fetuses in the proceedings. I called Walter Mark Anderson III, a retired judge who began the practice, and told him the news. “That’s fantastic!” he exclaimed. Before fetal attorneys, he explained, girls “came in, said this, that, and the other…and nobody really questioned her.” The new law also requires district attorneys to cross-examine minors seeking a bypass—making the hearings, which are supposed to be fact-finding exercises, more like criminal trials. The judge may adjourn a hearing for as long as he sees fit, and he may disclose the minor’s identity to any person he determines “needs to know.” If a minor’s parents become aware of the petition, which the Supreme Court intended to be confidential, they are entitled to participate in the hearing and be represented by a lawyer. On October 1, the ACLU filed a suit asking a federal court to stop the law from taking effect and rule it unconstitutional.

It’s been eight months since Kiera’s hearing, but the memory still sets her off. “I had to walk this total stranger through my life,” she recalls angrily. “I had to open up one of the most embarrassing parts of my life.” But she knows she was lucky. She has a friend whose dad used to hit her before she moved out of his house. If that friend got pregnant, Kiera asks, “should she ask him if she can have an abortion? Or should she go in front of a court that says, ‘I’m sure your parents would understand’? No, really, tell me—which should she pick?”

Since 2010, how have states have made it harder for minors to obtain a judicial bypass?