With a cheery drawl and an expression somewhere between exhausted and dead-eyed, Lindsey Graham spent a Sunday morning in November rattling off the greatest hits of GOP impeachment conspiracy theories before most Americans had finished their second cups of coffee. “When you find out who the whistleblower is, I’m confident you’re going to find out it’s somebody from the Deep State,” the South Carolina senator insisted during Fox News’ 10 a.m. block. Graham, a former Trump foe who has become the president’s chief defender in the Senate, then shifted into attacking Democratic Rep. Adam Schiff, the House Intelligence chair and now lead impeachment manager. “If you think Schiff is looking for the truth,” Graham snarled, “you shouldn’t be allowed to drive anywhere in America, because that’s a ridiculous concept.”

The appearance capped off what could only be described as a banner week of bullshit from Graham—though from his point of view, the Democrats were the ones spouting nonsense. “I think this is a bunch of BS,” Graham told reporters, saying he wouldn’t read witness testimonies released by Schiff’s committee. As for the House’s “sham” impeachment proceedings, which Graham would soon inherit: “I’ve written the whole process off.”

A day later, Jaime Harrison, Graham’s likely Democratic opponent this fall, entered the tiny, cinder block–walled dining hall at Clinton College, a small, Christian, historically black school in Rock Hill, South Carolina. Wearing gray dress pants and a black V-neck sweater, his head shaved bare, Harrison stood before a row of square laminate bistro tables, where two dozen students, mostly from the school’s student government, drum line, and cheer team, sat waiting to hear him speak.

But when the 44-year-old Harrison did, he made scant mention of his opponent. Instead, as the smell of greasy breakfast hung in the air, Harrison asked the students about their passions and majors, encouraging them to find mentors who could help yoke the two together into a career. Harrison didn’t say much about national politics, alighting on it for only a few minutes as he connected the dots between voting, policy in Washington, and the student loan burdens many in the room would soon carry.

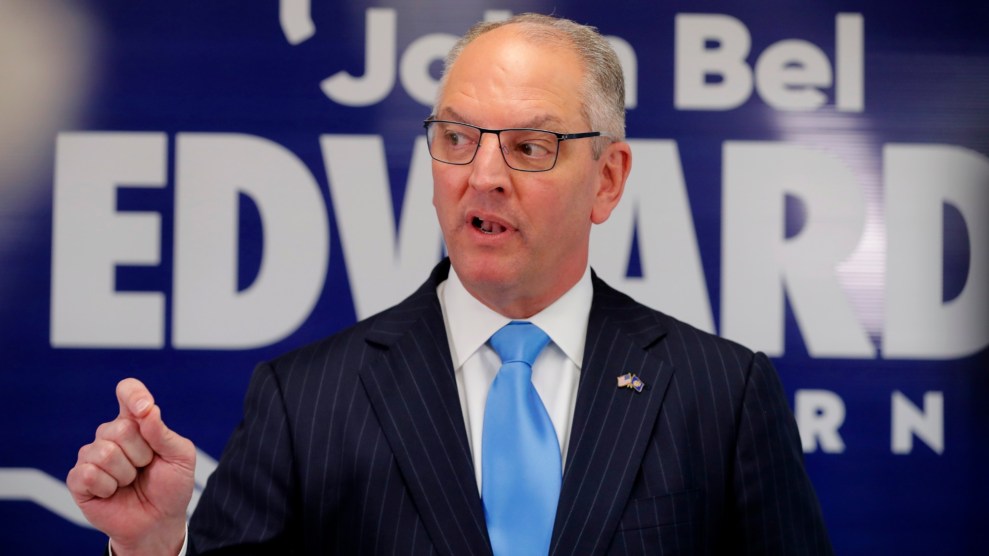

Jaime Harrison at Finlay Park in Columbia, South Carolina.

Swikar Patel

“Part of my thing is taking advantage of the opportunity,” Harrison tells me afterward in his baritone Southern lilt. “It’s not every day [that students meet] a younger politician who understands the same trials and tribulations that these kids are going through.”

At first blush, Harrison’s meet-them-where-they-are approach might look like a misstep when running against such a prominent—and lately notorious—DC figure. Over three terms in the Senate, Graham had cultivated a reputation as a staunch conservative who delivered bipartisan agreements on immigration and climate change—part of his identity as self-described “political wingman” to Arizona Sen. John McCain. (McCain had affectionately referred to his close ally as “Little Jerk.”)

But three years into the Trump presidency, Graham, who said during the 2016 election that he wished Republicans had kicked Trump out of the party, has become one of the president’s main sycophants. The reversal has earned him a particularly brutal impersonation from Saturday Night Live’s Kate McKinnon, whose sweaty Graham explains in a recent sketch that “even my bodily fluids are trying to distance themselves from me.”

There’s a method to Graham’s about-face. Surfing political trends is part of it: As the Republican base gravitated toward Trump, Graham followed suit. But maybe it’s more about Graham’s desire to remain close to power; a Republican strategist recently likened him to a “pilot fish” in Rolling Stone—“a smaller fish that hovers about a larger predator, like a shark, living off of its detritus.” Put more generously: “It’s better to be at the table than on the table,” says Matt Moore, former chair of the South Carolina Republican Party.

But Graham is also contending with a South Carolina that’s tinging bluer. And Trump’s presidency has seen a spate of Democratic wins and near-misses in the unlikeliest corners of the South, gains that relied on a formula of increasingly blue cities, party-flipping suburbs, and turnout of black voters. Harrison, a longtime Democratic operative and current Democratic National Committee associate chair, advised Democrat Doug Jones’ successful Senate campaign in Alabama. Now it’s Harrison’s turn to put his own strategies to the test.

“I think [the Democratic spirit] is alive and well all across the South. The real question is getting people to believe that it’s possible here,” Harrison says. “People have a little sliver of hope, and now it’s important for me to take that sliver and turn it into a roaring flame.”

Sixteen-year-old Patricia Harrison gave birth to Jaime on February 5, 1976; his father was never around much, and fully disappeared when Jaime was 10. Raised mostly by his grandparents in their mobile home in Orangeburg, South Carolina, a majority-black city about 45 minutes outside of Columbia, Harrison spent part of his childhood on food stamps, and some of it homeless. “My grandparents didn’t have much, but they raised me right,” Harrison said in his video campaign announcement.

Television delivered Harrison his model for an ideal life: The Cosby Show’s Huxtable family. He wanted what they had: “A middle class life—a nice house, a beautiful wife who’s a lawyer who spoke Spanish—that’s what I wanted.” None of his caretakers had finished high school. But “when [Denise] went off to college, I wanted to go to college.”

Those fictional role models were bolstered by real mentors. There was Ms. Fersner, the guidance counselor who Harrison worked for as a personal assistant and who taught him about the fee waivers that would let him take the SAT for free. There was Ms. Harrold, the AP calculus teacher with whom Harrison, a self-described nerd, chose to spend most of his lunch periods. Harrold also advised the school’s chapter of the National Honor Society and encouraged Harrison to run for president of the group’s regional board.

At an Honor Society event, Harrison met his future political mentor, James Clyburn, who’d just been elected to the US House—the first black South Carolinian elected to federal office in almost 100 years. “I told him I wanted to work in his office one day,” Harrison recalls. “He kind of laughed and said, ‘Well, you’ll need to go to college.’”

Harrison ended up at Yale, and then as a law student at Georgetown in 2003, he found his way back to Clyburn. In 2006, when Clyburn became leader of the House Democratic Caucus, he made Harrison executive director—the caucus’s youngest ever. And the next year, when Clyburn became the Democrats’ whip, Harrison ran vote counting for the party.

The day after Harrison’s appearance at Clinton College, I drive him from Denmark Technical, another historically black college, to Charleston, while he runs through the personalities he contended with in Congress. “We had Rahm [Emanuel], we had Steny [Hoyer], we had [Nancy] Pelosi,” he says, “and we had a large freshman class.” There were the influential subgroups, like the fiscally conservative Blue Dog Coalition, the Congressional Black Caucus, and the Congressional Hispanic Caucus. “Any group could tank a bill,” Harrison says. “One thing I’m proud of: We never lost a party-line vote on the floor. It may not have been the bill everybody wanted, but it was the best we could do for a very diverse caucus.”

Harrison says his time whipping votes gave him an “old, pragmatic” way of looking at the political process. “I’ve never seen a bill that started one way and looks exactly the same coming out,” he says. “It just doesn’t happen.” He brings the same gimlet eye to the Democratic presidential primary. “In the end, all of these proposals that candidates are talking about—none will look the same way once it goes through the process,” Harrison says. He’s equally wary of the efforts among progressives to replace incumbent Democrats with more liberal members. “Why spend your resources fighting with someone who agrees with you 97 percent of the time and not use those resources to go after a Peter King in New York or a Jim Jordan in Ohio?”

After five years in Clyburn’s office, Harrison left to join the Podesta Group, where his lobbying clients read like a progressive “most wanted” list: Walmart, the biotech giant Amgen, the pro-coal American Coalition for Clean Coal Electricity, General Dynamics, and Boeing.

His tenure there might not earn him accolades from the rising left, and when I mention this, his amiability wanes, and he takes a serious tone. “There’s nobody who can out-progressive me in terms of understanding the hardships of poverty,” Harrison says. “I’ve known it, I’ve seen it, I’ve touched it, I’ve tasted it, I’ve eaten it my entire life. And when I go into communities, poor black folks look at me and say, ‘Jaime, I would be so blessed if I can raise my kids and they grow up to do the things you’ve been able to do.’” Harrison won’t disclose how much he earned at the Podesta Group, but he used his salary to pay down $160,000 in student loan debt and take care of his mother’s bills.

“This purity test—it’s a fictional, made-up thing,” Harrison says. “We get so caught up in the politicking, and we forget about the reality of life in these communities.” He repeats an example he often gives on the stump: “We talk about a $15 minimum wage, and that’s great. But I had a conversation once with my cousin, and he said to me, ‘Jaime, I hear Democrats talking about that, and yeah, I would love to make that. But how can a brother just get a job?’”

Harrison’s campaign tries to directly address those issues, integrating community service with retail politics under its “Harrison Helps” initiative. The candidate, staff, and volunteers plan to travel around the state hosting events such as resume workshops and seminars for homebuyers. In August, Harrison’s team assembled 400 backpacks full of school supplies for students in his hometown of Orangeburg. The week before Christmas, volunteers served meals to families at the Ronald McDonald House in Charleston. Harrison’s grassroots campaign echoes the 1988 presidential primary race run by Jesse Jackson, who has voiced support for Harrison’s efforts.

“Jaime seems to be the first candidate who has found a way to merge the sort of corporate Democratic Party support and the grassroots support,” says Moore, the former South Carolina Republican Party chair, who counts Harrison as a good friend.

On the trail, Harrison generally tries to avoid what he calls a “DC-oriented frame” of Democrat vs. Republican and instead talks about right vs. wrong. “I always say, interests live in your head, your values live in your gut and your heart,” he says.

Accordingly, you won’t hear him talk much about Graham. “We can use the fire of the anti-Lindsey [sentiment], but you can only use that to an extent,” Harrison tells me. “I always believe Democrats win when we can be hopeful and aspirational, not just tearing somebody down.” The most mention of Graham I heard was in front of a group of Charleston-area Democrats. They’re obsessed with Graham’s antics, Harrison says. (He’s right: The mostly white audience erupted into laughter and applause when Harrison mentioned his campaign is selling novelty Lindsey Graham flip-flops.)

The campaign’s focus groups have found that white women in South Carolina are skeptical of Graham because of his “continuous extreme flip-flopping on issues.” They were especially turned off by his tepid defense of McCain after the president’s postmortem attacks. Harrison’s campaign announcement video, titled “Character,” contrasted clips of Graham calling Trump a “race-baiting, xenophobic, religious bigot” with Graham later declaring the opposite. “Here’s a guy who will say anything to stay in office,” Harrison says to the camera, accusing Graham of having “traded his moral compass for petty political gain.”

In the summer of 2017, DNC Chair Tom Perez called Harrison for advice. Harrison, coming off four years as chair of the South Carolina Democratic Party, had lost his bid to lead the national party earlier that year. But Perez had given him a meaty consolation prize—an associate chair position tasked with developing the party’s Southern strategy.

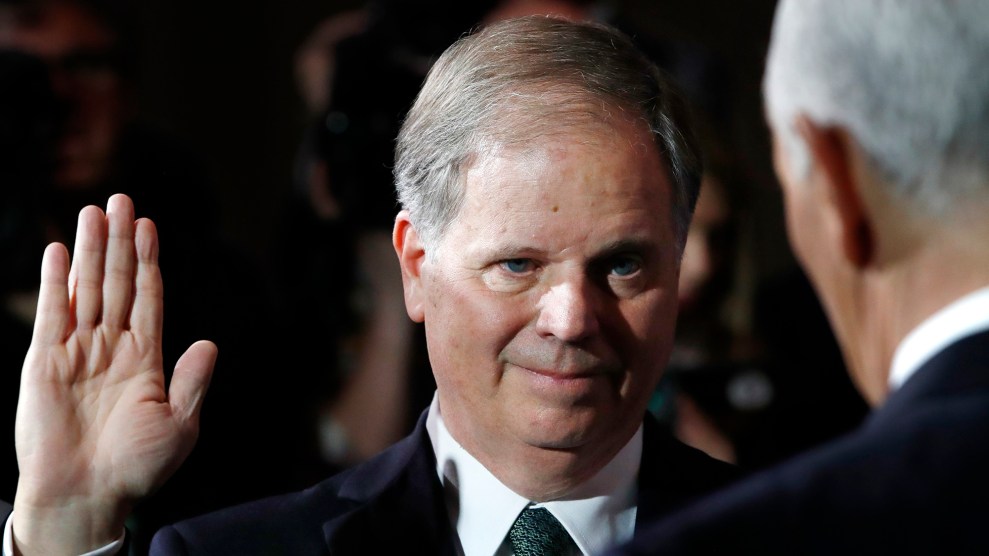

Harrison’s first test would be helping Doug Jones, a former US attorney who had been at the helm of some of Alabama’s most important civil rights victories, and who was running in a special election to replace Sen. Jeff Sessions. Perez, who overlapped with Jones at the Justice Department, knew he had a good candidate in him, and, thanks to congressional Republicans’ incessant attempts to repeal the Affordable Care Act, also had a favorable political landscape. (This was before the accusations of child molestation against Republican candidate Roy Moore.)

Jones has a contentious relationship with the Alabama Democratic Party and Joe Reed, a powerful black political leader who’d long been among the party’s key power brokers. He needed a strategy to turn out black voters (above and beyond courting Reed), who account for more than a quarter of Alabama’s population but whose votes had been particularly depressed by voter-ID requirements and felon disenfranchisement.

Harrison and a few DNC staffers went down to Alabama that July and presented Jones with a blueprint he’d tested during a House special election in South Carolina. “I talked about the divisions within the African American community—and not so much divisions, but the different groupings, the older African Americans, African American women, younger African Americans, and the things that motivate them,” Harrison says.

“He emphasized how important it was to work alongside local folks who really understood that black voters aren’t a monolith,” Doug Turner, a senior adviser for Jones’ campaign, recalls. The advice proved crucial: Jones narrowly won, largely due to black voters, whose almost 30 percent turnout rate eclipsed previous Alabama Senate elections. “The votes are here,” Harrison says. “The question is, can we change the mentality?”

Other models from across the South also give Harrison confidence. Last November, Democrat Andy Beshear defeated Kentucky Gov. Matt Bevin, who’d hitched his wagon to Trump in a state the president had won by 30 points. “Tonight’s big Democratic wins,” Harrison said in a statement after Beshear’s victory, “prove that a New South is truly rising.”

But can Harrison replicate that magic back home? In 2018, attorney Joe Cunningham flipped a South Carolina congressional seat blue for the first time in nearly 40 years. A lot went into Cunningham’s victory—a climate change platform informed by Charleston’s near-weekly tidal flooding; his promise to deny Pelosi the House speakership; a far-right GOP challenger sidelined by a car accident—but especially recent transplants to Charleston from bluer states. More than 80 percent of the state’s population growth comes from people moving from out of state, according to Charleston’s Post and Courier. The population’s racial makeup has stayed stagnant, but its generational makeup has changed considerably: The senior population in South Carolina is among the fastest-growing in the nation.

“Can Jaime Harrison do statewide what Joe Cunningham was able to do in the 1st Congressional District? They both have appeal in suburban areas and the benefit of going up against candidates who have steered hard to the right,” says Gibbs Knotts, who teaches political science at the College of Charleston. “I’m not one who thinks things are shifting way left, but there is a lot of opportunity with the changing demographics in the state.”

There’s “definitely a reconfiguration and scrambling of the winning coalition,” says Joe Trippi, a longtime Democratic strategist who worked on Jones’ campaign. Fiscally conservative voters, college Republicans, and Republican women are all more willing to give Democratic candidates a second look—especially, Trippi says, a moderate like Harrison: “The more that Lindsey Graham becomes part of the big fight of everyone going to their corners, those women and those younger Republicans are looking for someone to bridge the polarization. That’s where there’s an opening for someone like Jaime.”

During the last months of 2019, Harrison’s campaign says it raised more than $3.5 million, a record quarter for any candidate in South Carolina history. In December, a poll showed Harrison only two points behind Graham. Still, Trump won the state by 14 points, and another state poll shows Trump trouncing any hypothetical Democratic opponent there in 2020. Harrison may have ended the year with a massive fundraising haul, but his total raised during 2019 is still at least $5 million behind Graham’s. “To characterize this as a long shot would be accurate,” Knotts says.

Harrison’s biggest hurdle is a lack of name recognition. His “job is to make sure that he becomes a household name,” says Clay Middleton, a fellow South Carolina DNC member and Clyburn alum, “or at least a name that most people would recognize.” To achieve that, Harrison plans to follow a prescription he got from former Georgia gubernatorial candidate Stacey Abrams. “Stacey’s advice to me was, ‘Jaime, you gotta go everywhere. You can’t give up on anybody,’” Harrison tells me.

“You can win in the South, but in order to win, you have to invest,” he adds. “You have such large pockets of African American voters, and the big thing is you have to persuade them that an election is important enough for them to come out and vote.”