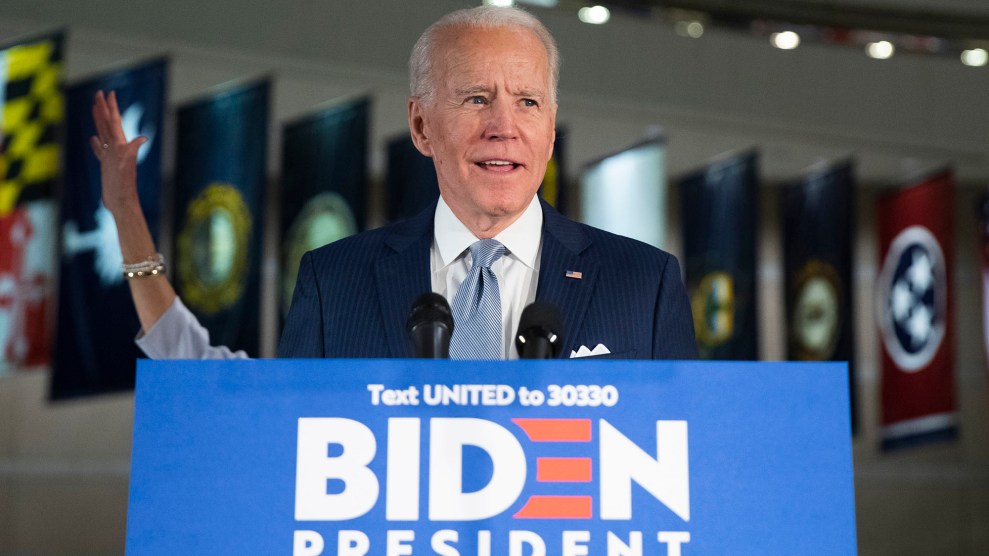

Jeremy Hogan/Sipa via AP

Rashad Robinson recalls feeling like a “pariah” in Washington during the earliest days of the Black Lives Matter movement. The executive director of Color of Change, the nation’s largest online racial justice organization, had been pressuring President Obama to address police brutality in the wake of the death of Michael Brown, an unarmed Black teenager murdered by police in Ferguson, Missouri, in 2014. “I felt a lot of negative heat,” Robinson recalls, “and was treated as a radical even by some Black people inside the Obama administration.”

Five years after Brown’s death, President Obama included Color of Change on a list of resources for people looking to learn more about systemic racism and invited Robinson to join him in a virtual roundtable discussion on police reform. And activists like Robinson had a wholly different reception among Democrats running for president over the past year. No longer “pariahs” or “radicals,” 2020 hopefuls courted progressive Black activists and asked them to weigh in on platforms that elevated their movement’s priorities. Those policies were showcased at first-of-their-kind forums dedicated to addressing environmental justice, mass incarceration, and the needs of women of color.

But Joe Biden was noticeably absent. Biden skipped several of those forums, put little muscle into developing a race-conscious agenda, and didn’t reach out to activist groups that other campaigns had pursued. None of that mattered for securing the nomination: Biden won the South Carolina primary, the cycle’s first test of Black support, with more than 60 percent of the Black vote. His competitors, meanwhile, delivered their visions for Black America to predominantly white audiences, proof that all the best intentions paled in utility to the trust Biden had built up during his four decades in federal office.

The Democratic primary is over, and a nesting doll’s worth of crises has assumed its place. Black Americans have been killed by COVID-19 at alarming rates and the burden of “essential work,” such as health and child care, has primarily fallen on them. Then, the constant drumbeat of police brutality erupted onto the national stage by the police killings of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor.

And now, the racial justice reforms that had found their way onto progressive presidential candidates’ platforms match those that protestors are demanding at demonstrations not just in major cities, but also in the unlikeliest of small towns across the country. And those closely aligned with the movement wonder whether Biden will take a page from his fallen opponents’ policy ideas—and if the younger, progressive Black activists who helped to author them will have a seat at Biden’s table.

“Those protestors can be voters,” says Aimee Allison, the founder of She the People, a national network of women of color. “We have got to get Trump out of office, but if that’s replaced with someone who doesn’t have a clear vision for racial justice, we won’t have a thing for Democrats to prove that there is a will, a heart, and a plan.”

The Black Lives Matter movement began in the wake of the death of Trayvon Martin, a Black teenager murdered by a white neighbor in 2012, and garnered nationwide attention following Brown’s 2014 death. Though the movement’s genesis had been in race-based violence, activists aimed to elevate all the layers of systemic racism and white supremacy that imbued the experience of Black Americans. That included drawing attention to discriminatory lending practices, environmental neglect in Black communities, and high maternal death rates among Black mothers in addition to police brutality and high rates of arrest and incarceration. While legacy civil rights groups like the NAACP opted to work closely alongside elected officials and corporations to push for steady, incremental change, Black Lives Matter preferred to work outside the system through demonstrations and social media-driven campaigns.

The movement’s demands went largely unanswered by the Obama administration, and during the 2016 election, it refused to endorse either Bernie Sanders or Hillary Clinton. It was “too early in the genesis of the movement to rally around anyone in particular who hasn’t demonstrated that they feel accountable to the Black Lives Matter movement,” Alicia Garza, a co-founder, said at the time. Instead, activists showed up at campaign stops to protest the candidates’ unwillingness to connect systemic racism to the economic disadvantages the Black community faced. In August 2016, the Movement for Black Lives—the coalition of organizations aligned with Black Lives Matters—issued a vision document that called for divestment from the criminal justice system, economic reform, and reparations.

As another presidential cycle began, those demands remained unchanged. But the willingness of Democratic candidates to engage did. Bernie Sanders leaned on the advice of Black scholars and activists to add a racial justice lens to his war on the rich. Elizabeth Warren’s trove of plans to combat racial inequality had been authored in partnership with progressive Black women activists and earned her their coveted endorsements. For the first time ever, on subjects such as criminal and environmental justice, “candidates were forced to have platforms and speak to them,” says Sen. Cory Booker (D-N.J.), who centered his own presidential run on racial inequality. “There were countless articles pointing that out as a major deficit in their campaigns.”

Another sign of the movement’s growing political capital: its ability to undercut candidates who might have gotten more traction in prior presidential primaries. Activists showed up at events for former South Bend Mayor Pete Buttigieg, former New York Mayor Michael Bloomberg, and current New York Mayor Bill de Blasio to protest how their administrations had treated Black communities. No apology or plan could shake the stigma the attention left.

“The presidential primary was so different from any in history because several candidates were exposed around their hypocrisy around police violence and their treatment of Black communities in general,” says Monifa Bandele, an activist with Malcolm X Grassroots Movement. “When moments presented themselves for people who do harm to Black communities to run for higher office, we made sure it was known that they betrayed Black communities.”

Biden, meanwhile, skated by with a middling history. The running mate of the country’s first Black president spent the primary scrutinized for his record on busing, his collaborations with anti-segregationists, and his hand in the 1994 crime bill, legislation that ushered in an era of mass incarceration and heavy policing. He nearly announced his candidacy on the same day as the first-ever presidential forum focused on women of color, changing the date only after the faux pas had been brought to his attention. Activists I spoke with told me that while other campaigns heavily courted their input and endorsement, they didn’t hear much, if at all, from Biden.

The hurdles now facing Biden are altogether different than the ones he cleared in the primary. President Trump has fully decamped to the side of white supremacists, but channeling the energy of a movement is an altogether different task. “What we can achieve when we don’t separate politics from movement is a lot,” Allison says. “Democrats shouldn’t use language that talks about the movement as separate from themselves.”

Crucial to that, according to advocates I spoke with, is for Biden to invite more of the voices who progressive candidates leaned on to advise him. Even before this charged moment, the Biden campaign had been seeking counsel from legacy groups such as NAACP, but also so-called “new movement” organizations, such as Campaign Zero, a police reform campaign founded by Black Lives Matter activists, and Color of Change, the group Robinson leads. But Allison says how the campaign engages these groups is as important as who it engages with. “Elizabeth Warren made her campaign an on-ramp for activists that explored a co-governance model,” Allison says. “Joe Biden needs a really powerful plan to combat white supremacy, but he also needs to explore a governance model so it’s not just Joe Biden’s plan.” Allison adds that she’d like to see Biden do more to reach out to Black women activists, something akin to the event Biden held on Monday with Black ministers in his hometown of Wilmington, Delaware.

Policy, too, will be a major piece of it. During a speech in Philadelphia on Monday, Biden called on Congress to immediately pass laws to stop the transfer of military weapons to police departments, ban officers’ use of chokeholds, and establish strong use-of-force standards. He also promised to create national police oversight commission during his first 100 days in office, an end to “qualified immunity”—special protection law enforcement has from civil rights lawsuits—and reissued his call for community policing, an existing pillar of his criminal justice plan. In early May, his campaign released the Biden Plan for Black America aimed at rectifying the economic and health care disparities the COVID-19 crisis put on full display.

But activists say it will take more than that. “The bar is higher than what it would have been a few years ago because we’ve gone through the years from Ferguson until now,” says Maurice Mitchell, president of the Working Families Party, a progressive organization that has made major pushes around policing. Biden has not yet committed to the most pressing ask of many Movement for Black Lives allies: divesting from police. And while Biden has pushed for aspects of the 1994 crime bill to be dismantled, Mitchell thinks Biden should apologize for it altogether. “He could endear a lot of people to him if he showed how he planned to repair that harm and put forth a bold platform that puts communities before easy ‘law and order’ rhetoric,” he says.

Biden also might have to challenge institutions he’s often sided with. “There is no way to make police unions and Black people happy,” Mitchell says. “This is a ‘Whose side are you on?’ moment.”

Color of Change’s Robinson notes that Biden’s current plan for Black America doesn’t challenge corporate power. “To have a plan that does not dismantle power or influence is not a plan for racial justice.”