Mother Jones illustration; Zuma; Getty

“This is the day that the Lord has made. We have come to rejoice and be glad in it,” says the Reverend Raphael Warnock during his October 4 sermon at Ebenezer Baptist Church. It’s a normal Sunday, with Warnock’s usual opening line, but it’s not really normal.

Call it the new normal. The sermon is prerecorded; it plays on the church’s website. Any affirmations of “amen” and “yes, Lord” only emerge within individual living rooms, replacing what was once the underpinning of collective voices with silence. Warnock’s sermons now regularly ask his flock to find connection and community wherever they can, perhaps through church small groups on Zoom, and to continue filling themselves with the satiating word of God.

This particular Sunday, the pastor is also celebrating 15 years of preaching at Ebenezer, the historic Black church in Atlanta that was once home to Martin Luther King Jr. “I wouldn’t give nothin’, as our folks used to say, for the journey,” the reverend tells his congregation.

Where ordinarily there would have been a physical celebration in the church to mark the occasion, there is instead a six-minute video montage of the past decade and a half. In one scene, surrounded by people, the reverend declares with conviction, “Guns are not allowed in the state Capitol. But they want them in our churches and in our schools. Have you lost your mind.” (It is definitively not a question; in Warnock’s view, state lawmakers had lost their damn minds.) Minutes later, a photo of Emmett Till fills the frame, captioned “Hoodie Sunday,” transitioning to footage of the congregation, pastor included, their faces framed by soft cotton. “We’ve been here before—Emmett Till, Trayvon Martin”—he cries, enunciating each syllable of the names of the deceased—“profiled, hunted down, and killed for crossing some cultural arbitrary line.”

It’s clear from watching that church events blend easily with social justice ones; there are barbecues and voting rights events and speeches on the ills of mass incarceration, an issue particularly dear to Warnock, as his older brother was recently released from 22 years in prison for a nonviolent drug-related offense.

In another frame, the late Rep. John Lewis, who was a congregant, sits beside Warnock in what looks like the Ebenezer sanctuary and they run swabs along the inside of their mouths to encourage Black men to get tested for AIDS; in another, Warnock is getting arrested at the Georgia Capitol building for protesting the legislature’s refusal to expand Medicaid.

Though it is not the point of the video, it has something of an inadvertent dual purpose—putting into striking relief why Warnock is celebrating his time at Ebenezer and simultaneously trying to become the first Black senator to represent Georgia. In many ways, he aims to do in the US Senate precisely what he has done at Ebenezer: live out his faith by serving and connecting with his community.

“I see politics as…one tool in the toolkit for the creation of a more blessed and beloved community that embraces everybody…for me, that is the work of the gospel, and a mandate that comes clearly from my faith,” Warnock tells me recently. “It’s a faith that does not allow me to hide behind stained glass windows, but to actually go beyond stained glass windows and the doors of the church and into the broader community—and yes, in this case, even engage in the swampy waters of partisan politics.”

But like his sermon that Sunday, nothing in this campaign is quite like what Warnock expected.

While Warnock typically keeps his eyes intently trained on the camera in his sermons, as if he’s willing his words to make meaningful contact, it’s just not the same as the in-person connection that’s long been a signature of his public service. And whether or not his message hits home is a crucial question not only for his flock and his individual campaign, but also for the Democratic Party writ large and for the entire country, as the party battles to take the Senate and the White House during a pandemic that’s killed more than 219,000 Americans.

The obstacles facing Warnock have not been small. First, there’s the history: Georgia voters have never elevated a Black person to represent them in the US Senate or the governor’s mansion, and even rising party stars like Stacey Abrams have failed (or, perhaps more accurately, have been injudiciously halted by a vote-suppressing state apparatus). Then there’s the pandemic: It poses an unprecedented challenge in getting people registered and to the polls—issues that Warnock worked on for many years in the Before Times—and in connecting with voters on the campaign trail, which now more often means through Zoom or Facebook Live. Another sobering consideration is that the demographic Warnock is best primed to naturally capture—Black voters—are among the people who are suffering and dying at the highest rate from the coronavirus. Warnock must also navigate the mounting complexities of actual voting, thanks to the current governor’s long history of voter suppression and recent messy battle over the state’s voting machines.

On top of all that—yes, there’s more—is the shape of the race itself: Warnock is competing in a jam-packed special election to replace former Sen. Johnny Isakson that features more than 20 candidates. This includes two prominent Republicans, Rep. Doug Collins and Sen. Kelly Loeffler, who was appointed to the seat in December—as well as Democrat Matt Lieberman, who is polling just high enough to possibly play spoiler and block Warnock from earning a majority and outright victory on Election Day and force a January runoff. And then, there’s getting out the vote in January when there’s no national draw to the ballot—and, well, that’s a horse of a different color.

It’s all a lot.

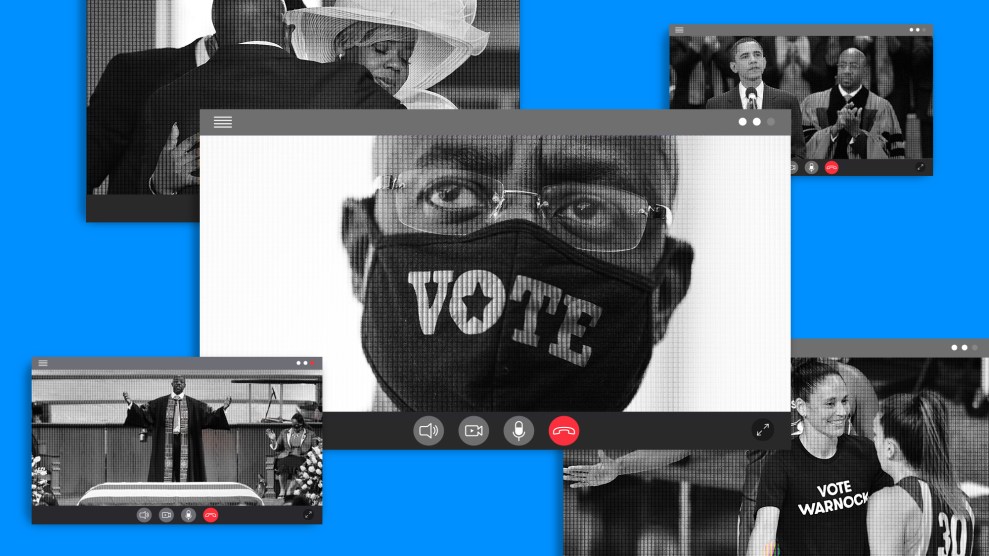

But unlike almost everything else in 2020, things are actually looking up for Warnock: Over the past couple months, partly due to grim circumstances, Warnock has cultivated a national profile. He delivered a stirring eulogy for Lewis when the civil rights icon passed away from cancer this summer. And following the police killing of George Floyd in May, VOTE WARNOCK began appearing organically on national TV screens—via T-shirts worn by WNBA players protesting Loeffler, who is also co-owner of a WNBA team and who made odious comments about Black Lives Matter. More recently, after the death of Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, money started pouring in from terrified, grieving Democrats to Warnock’s war chest, placing him ahead of all his opponents in fundraising. This was followed by endorsements from former presidents Barack Obama and Jimmy Carter, as well as Abrams. All of this has boosted Warnock to lead the crowded field in many polls this fall, and for his once long-shot bid to be considered a toss-up.

“The character of our country, the soul of the nation hangs in the balance,” Warnock tells me. But, he adds, “the best saints actually get their hands dirty. John Lewis embodied that—it’s not a kind of saintliness that stays out of the fray, it gets in the fray, it gets in good trouble.”

Do not mistake Raphael Warnock for a born-and-bred Atlanta Democrat. As he likes to remind people, he’s from Savannah, a product of the land beyond the deep blue metropolitan, from Georgia proper. His ads and campaign materials emphasize his mother’s deep Georgia roots—she grew up in a small town in the rural southeastern part of the state, where she picked cotton and tobacco during the summer months; his father is from rural Screven County. Campaign materials also highlight Warnock’s journey from a childhood in public housing, to Morehouse College, thanks to low-interest student loans and Pell grants, to Ebenezer, where 15 years ago he became the youngest preacher to take the place where Martin Luther King Jr. once stood.

There is a clear line from this pulpit, from loving your neighbor as yourself, to the core values of democracy. So it makes sense that many of Warnock’s energies, particularly over the past several years, have been channeled into helping people exercise their right to vote.

“The meaning of our covenant with one another is played out, and public policy seems to give more and more to the richest of the rich and less and less to the poorest of the poor,” he tells me. “After a while, that begins to cause the fabric of democracy to begin to fray, and if we don’t defend it, the voices of ordinary people will get crowded out of the process and become more and more disconnected from the process itself.”

Since its inception, Warnock has worked with the New Georgia Project, a nonpartisan voting rights organization founded by Abrams in 2014 that has registered some 400,000 new voters. (The group’s work also came up when my colleague Jamilah King was reporting on Abrams’ historic run for governor back in April 2018.) Billy Honor, the New Georgia Project’s director of faith organizing, tells me that “when there’s a moral case to be made, there’s a consistency of voice from Black communities and Black faith leaders that becomes the conscience of the nation”—reaching back from Frederick Douglass to Fannie Lou Hamer to the Reverend William Barber of the Poor People’s Campaign. Warnock, Honor notes, is of that tradition.

During the 2018 election cycle, Warnock and Honor together created a vote-by-mail initiative specifically geared toward Black churchgoers. The effort resulted, according to Honor, in the biggest vote-by-mail turnout in state history: More than 2 million votes were cast overall, with 184,925 of them by mail—more than double prior elections.

This year, the New Georgia Project is investing even more in digital outreach—training its volunteers to rally potential voters through social media, text, phone banking, and email. Ebenezer has also continued to finesse voter registration outreach during the pandemic, with registration reminders during online services, informational sessions about the state’s new voting machines, and, recently, a drive-thru picnic, where motorists were handed food and Icees through their car windows before they end up at a voter registration station.

For his part, Honor says he’s been continuing to focus on the “resiliency” of Black faith communities, working with pastors around the state to figure out the best way to reach out to congregations and get their voters to the polls. “Our election monitoring is not just about giving out water [this year], it’s not just about making sure people are ok,” Honor says. “It’s now also, ‘Do you have a mask?’”

Warnock, of course, is enmeshed in his own campaign, though it is similarly focused on these ideas and building wide appeal on health care—rural health care in particular. Beyond the failed coronavirus response, the campaign has been zeroing in on how the state’s decision not to expand Medicaid has led to a crisis and widespread loss of life, specifically among rural Georgians. Warnock is prone to mention his 2014 arrest at the governor’s office, where he was protesting the decision, as extra credibility: “My running for Senate is an effort to get escorted again by the Capitol Police, this time not to the central booking but to my new office as a US Senate senator, where I can do the work that I’ve been talking about all these years.”

This outreach caught the attention of Dr. Karen Kinsell, the only medical provider in Clay County, where about 30 percent of residents live below the poverty line. Kinsell has watched as smaller hospitals across the state have shuttered—three of them over the last decade within 60 miles of her practice—and now another in the county next to her is set to close before the election. She met Warnock over Zoom in September and was struck by his understanding of how challenging it can be for rural residents to get basic health care, let alone access to specialized medicine. “[Warnock] truly appears to understand some of the real problems facing everyday Georgians, and to have both reasonable solutions and a commitment to making these things happen,” she tells Mother Jones.

But really reaching those voters still poses a significant challenge. As Kinsell says, “People who aren’t into politics have no idea who most of these people are”—particularly in this crowded race. And, again, stump speeches and meet-and-greets and town halls just aren’t as effective over Zoom. Warnock’s campaign has tried to expand its reach by teaming up regularly with the Democratic candidate in this year’s other Georgia Senate race, Jon Ossoff. Warnock also began venturing out last month for socially distanced events with constituents, but it’s a tall order to navigate the entire state less than a month before Election Day.

There’s that saying in Southern politics that goes something like, if you scratch the surface of any political issue in the South, you’ll find that it’s about race. It certainly came as no surprise to Warnock that he would encounter racism in his bid to fill Isakson’s seat—he’s a Black man in Georgia—but that doesn’t make it any less egregious or any less trying.

In August, Warnock was in a Zoom meeting of the Hall County Democrats for less than a minute when the onslaught began. In the comments, vulgarities multiplied faster than Kim Copeland, chair of the Hall County Democrats, could delete them. The n-word was prevalent, the racist slurs endlessly copied and pasted into the chat. It escalated into videos featuring swastikas and a Nazi flag, faceless masturbation, and other atrocities. Copeland and Warnock decided to cut off the event and reschedule; many people had logged off in horror, anyway.

In a screenshot sent to Mother Jones, Warnock looks profoundly sad; his mouth is slightly ajar, his eyes betray pain. Politics may be somewhat new territory, though the racism is all too familiar. Even before the Zoom attack, I noticed the Ebenezer Facebook page was on the receiving end of poisonous, racist attacks from people who are angry that Warnock is running for office. Years ago, a few weeks after a white supremacist killed nine congregants at Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church in 2015, a couple of white boys left Confederate flags strewn across the campus of Ebenezer Baptist Church. “It was an attempt to intimidate, to clearly send a message just weeks after Mother Emanuel, but we won’t be intimidated or turned around by that kind of thing. It just demonstrates the need for us to amplify our voices around unity, inclusion, and a love that is courageous enough to embrace everybody,” he says.

Similarly, the Zoom incident, Warnock says, “really underscores the importance of our work and our movement…It won’t stop us from going everywhere to speak to everyone.”

This, for better or worse, has made Warnock the perfect foil for his top opponent, Loeffler. While she began her tenure in the Senate with a reputation for being a moderate Republican, an educated, elite Atlantan, she’s pivoted hard to Trumpism, recently claiming in a campaign ad to be more conservative than Attila the Hun, who, incidentally, was also known as “the Scourge of God.” Just last week, she accepted the endorsement of Marjorie Taylor Greene, who is the favorite to represent Georgia’s 14th District in the House come November and a far-right conspiracy theorist.

As part owner of the WNBA’s Atlanta Dream, at one point Loeffler was reportedly deeply involved with the team, building her work travel schedule around games and hunkering down with the head coach after games to review plays and stats. When Floyd was killed by a police officer this summer and the WNBA dedicated its season to the Black Lives Matter cause, Loeffler publicly opposed the move, writing a letter to WNBA Commissioner Cathy Engelbert expressing her displeasure. “The truth is, we need less—not more politics in sports. In a time when polarizing politics is as divisive as ever, sports has the power to be a unifying antidote,” she wrote.

The team and the entire player’s union was furious—particularly Elizabeth Williams, a forward for the Dream, and Sue Bird, the 11-time all-star guard for the Seattle Storm, both of whom occupy leadership positions. What quickly became clear, Bird told me during a recent press conference, was that the louder they were, the more Loeffler benefited politically: “What better way to rile up your base than to show you’re against a league full of Black women who are standing here saying ‘Say Her Name’ and ‘Black Lives Matter,’ while simultaneously being able to say, ‘Oh, but look, I’m helping women and women’s sports by owning a team.’”

The players began researching candidates in the crowded primary, and Bird suggested they publicly back Warnock. “We did a lot of vetting, having conversations directly with Rev. Warnock on Zoom calls to make sure our values aligned,” Bird says. “This wasn’t just, ‘Oh, we’re going to support whoever’s on the other side.’ This was a deep dive into whether this was a candidate we connect with.”

Starting on August 4, Dream players sported black T-shirts with VOTE WARNOCK emblazoned across the front to their nationally televised game against the Phoenix Mercury. Many others in the league soon followed. The move boosted Warnock’s profile substantially; two days later, his campaign reported that it had gained 3,500 new donors. From there, the numbers kept climbing until Warnock had the biggest donation numbers of anyone in the race.

“I’m very proud of the women of the WNBA who stood up, refused to allow their voices to be silenced,” Warnock tells me. “I think they saw me as a kindred spirit—it was a very proud, powerful moment for me.”

Despite all these trials and tribulations, or maybe because of them, it actually makes deep sense that a man of faith like Warnock is running for office in this moment. One of my first conversations with Warnock took place on August 25—not two full days after another Black man, 29-year-old Jacob Blake, was shot several times in the back by a police officer in Kenosha, Wisconsin. Warnock tells me that the cycle of Black people being shot by police, and then searching for ways to comfort and guide his congregation through their grief and fear, is “exhausting.” Considering the toll the pandemic has taken on Black communities, paired with the inability to gather and process the trauma of police violence, is excruciating, he says. But, he also insists, it’s never defeating.

“It takes a toll on the collective psyche of the nation to see Black lives hunted down and killed like wild prey on American streets,” he says. “Some communities get so demoralized that their people may get into a sort of nihilism that says, ‘Well, what do I have to lose after all?’ I don’t know what other politicians mean when they speak about the soul of America, but that’s what I’m talking about—the spiritual health that enables you to keep fighting for the best, even in the midst of the worst.”

Just a month and a half later, he’d be celebrating his anniversary at Ebenezer, looking back at the reel of activity, of pain, of joy. Toward the end of that video, Warnock addresses his congregation on the subject of the pandemic. “We’ve never seen anything like this.” A new threat, which now exists alongside all the old ones. Still, Warnock concludes, “We shall overcome…someday.”

Images from left: Curtis Compton/TNS/Zuma; Alyssa Pointer-Pool/Getty; Elijah Nouvelage/Getty, Barry Williams/Getty, Julio Aguilar/Getty

This article has been updated with a correction: Rev. Warnock began working with the New Georgia Project at its inception in 2014.