Mother Jones illustration; University of Michigan; Wikimedia

Two years after the 2008 financial crisis, a government commission began releasing their findings on the causes of the worst economic downturn in nearly a century. In 19 public hearings and through 663 pages of text, the investigators faulted an array of players, including financial institutions and multiple presidential administrations. But a major focus of blame fell on the government regulators that had allowed mortgage-lending standards to collapse, leading to the financial ruin of major banks and hundreds of thousands of households.

One such regulator was the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency, a little-known federal office charged with supervising nationally chartered banks. The commission concluded the OCC had spent years protecting its authority by working to quash state efforts to more tightly regulate the banks, “turf wars” that left sometimes-predatory financial institutions to carry on scot-free.

The OCC’s troubled history helps explain why today’s battle among Democrats over who should lead the agency through the current economic crisis has become so heated. The stakes are further heightened, consumer advocates say, because the OCC has powers that could mitigate racial inequities highlighted and exacerbated by the coronavirus pandemic.

In the run-up to the 2008 financial crisis, “the OCC really served the short-term interests of banks and bank profits instead of serving the public interest—which is what it is ultimately supposed to do,” says Rebecca Borné, senior policy counsel at the Center for Responsible Lending. “Now we’re at this moment where the country is at least attempting to reckon with systemic racism. This is an agency that has so much power to do good or harm when it comes to addressing systemic racism.”

“The last foreclosure crisis was in part caused by aggressive preemption by federal bank regulators” like the OCC, adds Lauren Saunders, associate director of the National Consumer Law Center. “This is an agency that does not have a tradition of putting consumer protection first and foremost, and it is critical that the person at the top be committed to that.”

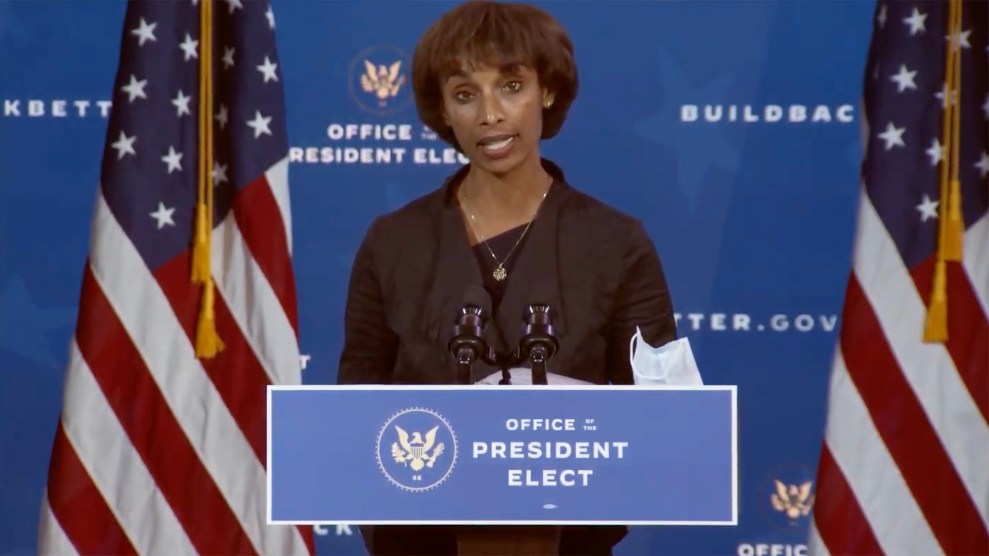

The two known contenders for the post—Michael Barr, a University of Michigan academic who worked in the Clinton and Obama administrations, and Mehrsa Baradaran, a law professor at the University of California, Irvine—both have long records studying financial regulation and inequality. But they have each come to represent different visions on the left for how to best approach banking regulation, particularly during an economic crisis that has widened racial wealth disparities.

While many Democrats see Barr as a solid choice, with broad experience moving equality-focused financial regulations through the Washington morass, some progressives worry his approach will prove too moderate and friendly to industry. They prefer that Biden nominate Baradaran, arguing that as one of the country’s foremost scholars on racial inequality in the financial system, she’s uniquely positioned to guide the OCC and to leverage its power to mitigate the racial wealth gap. Barr’s supporters says his record of advancing key consumer protections shows he is also up to that task. Both Baradaran and Barr declined to comment for this story.

The battle around the nomination has gotten so intense that Al Pina, a co-founder of the National Minority Community Reinvestment Cooperative, threatened to mount a hunger strike if Biden picks Barr over Baradaran, citing the need to build “true racial economic inclusion.” Multiple advocacy groups contacted by Mother Jones for this story did not want to speak on the record, out of concern that they’d be perceived as taking a side. It’s unclear when the administration will formally announce a nomination, but the Wall Street Journal reported last month that Barr is expected to be tapped for the job.

Progressive criticism of Barr cites his work on the Dodd-Frank act, the mammoth overhaul of Wall Street regulations enacted in response to the 2008 financial crisis. As an assistant treasury secretary under Obama, Barr was a key architect of the law. In that role, Barr reportedly opposed the most stringent limitations on big banks envisioned by some Obama officials and lawmakers, including the strictest versions of the Volcker Rule—part of Dodd-Frank that bars financial institutions from engaging in riskier forms of investing. While Bloomberg described him at the time as a Wall Street “nemesis” because he defended a version of the rule banning banks from investing in hedge funds, in her 2013 book, Sheila Bair, the former chair of the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, mentions an effort by Barr to water down the rule and to convince Congress to include loopholes that would allow future bailouts of financial institutions.

Progressives also take issue with Barr’s private work in the burgeoning financial technology sector, where he has advised a venture capital firm that has bankrolled related start-ups, and a trade group that advocates industry friendly regulations. Barr has also advised Ripple, a digital currency platform whose top executives were hit with a Securities and Exchange Commission lawsuit after his work there. A major decision the OCC will face in coming years is whether to grant FinTech firms bank charters, which would exempt them from regulation by state authorities who tend to impose stricter interest rate limits—a move that would pave the way for predatory lending, explains Saunders. Given these links, some progressives question Barr’s allegiances to the sector.

Barr’s defenders point to his record of advocating for banking reform, and to his role in helping establish the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau—the financial watchdog created by Dodd-Frank and the brainchild of Sen. Elizabeth Warren, herself a vocal foe of big banks. In her 2014 book, Warren called Barr a “behind the scenes hero” of the Dodd-Frank fight, notes Jesse Van Tol, the CEO of the National Community Reinvestment Coalition. He also says criticism of Barr’s role in stymieing a stronger Volcker rule from being included in that bill is “misplaced,” since parts of the initiative fell apart during congressional negotiations after it was linked to an exemption crafted by Republicans aimed at weakening CFPB oversight over auto dealers. As for Barr’s ties to FinTech, Van Tol says Barr was hired to advise the firms on consumer protection and financial inclusion—issues linked to Barr’s scholarship on the unbanked and the potential of digital innovation to improve access to financial services.

Barr’s supporters also point to past initiatives he’s been involved with that aimed to bring financial equity for marginalized populations, including the role he played in the Clinton administration’s building of the Treasury Department’s Community Development Financial Institution fund, which invests in financial institutions serving low-income communities.

Many progressives argue Baradaran is better positioned to push the OCC on issues of financial inclusion because they not only have been the central focus of her scholarship for decades—she’s written two acclaimed books and countless articles on the subject—but also a part of her own life, as a first-generation American who arrived in the US as a refugee.

“Baradaran’s own experiences make her uniquely qualified to understand what many Americans living on the margins are going through,” wrote Reps. Ayanna Pressley (D-Mass.) and Jamaal Bowman (D-N.Y.) in an op-ed last month. “[S]he has the resolve to tackle the historical policies and practices of financial oppression against Black and brown communities.”

Progressives also see Baradaran’s expertise on the racial wealth gap as something that can be harnessed to reverse the damage wrought by the OCC under Trump. Last year, for instance, the agency finalized a rule that weakened the implementation of the Community Reinvestment Act, a key civil rights law requiring banks invest in communities harmed by financial discrimination. The new rule made it easier for banks to meet the law’s requirements without substantially investing in communities of color. In the last year of the Trump administration, the agency also issued two rules that will help non-bank lenders avoid state regulators and give out loans at exorbitant rates—a change that is likely to hit minority communities, who are often targeted by high-cost lenders, the hardest.

Erin Lockwood, a political science professor at UC Irvine who has studied the 2008 financial crisis, says progressive enthusiasm for Baradaran over Barr likely has something to do with the break she would represent from the traditional Washington approach to financial regulation, a system Lockwood describes as “preventing banks from doing bad things” rather than taking proactive steps that could lessen inequality.

Many of the ideas that Baradaran is best known for—she has called for a postal banking system as a way to advance financial inclusion, for instance—would represent a shift in vision about what a banking regulator should push to accomplish: “Not just stopping banks from doing bad things, but getting them to do good things,” Lockwood says. “I think there is a lot of enthusiasm that maybe this would be a chance to think about the role of regulation as positively advancing racial equity, as opposed to just stopping discrimination.”