Missouri Attorney General Andrew Bailey speaks to reporters in May.Kacen Bayless/The Kansas City Star/Tribune News Service/Getty

Update, July 21: On Thursday, in a unanimous decision, the Missouri Supreme Court ruled that state Attorney General Andrew Bailey overstepped his authority when he refused to approve the fiscal note for the abortion-rights ballot initiatives proposed by retired pediatrician Anna Fitz-James. Bailey’s stonewalling “cannot be justified,” Judge Paul Wilson wrote, affirming a lower court order directing Bailey to approve the fiscal note within 24 hours. “Fitz-James’s constitutional right of initiative petition is being obstructed, and the deadline for submitting signed petitions draws nearer every day.”

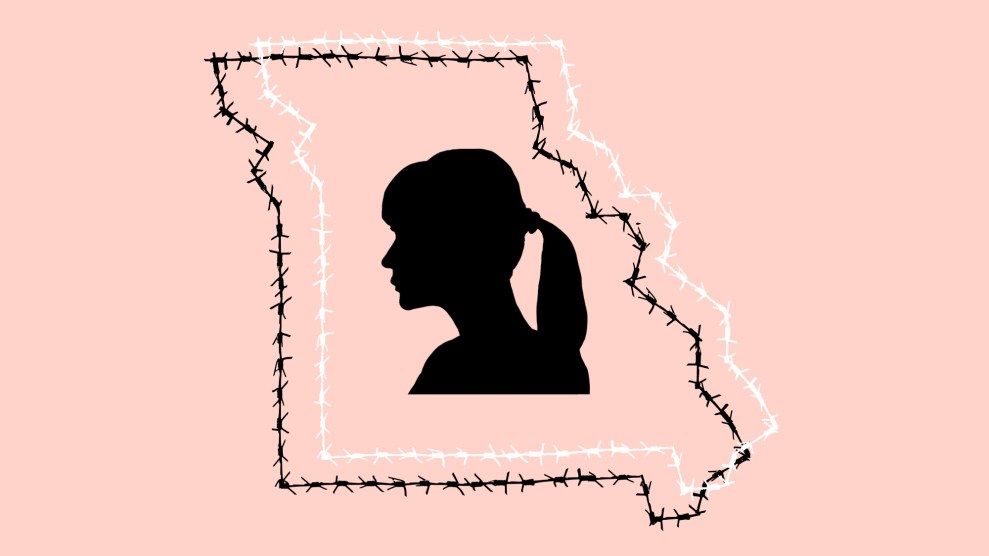

In May 2019, when Missouri banned abortions at or after eight weeks of pregnancy, abortion-rights advocates decided to put the issue to voters. Under their state constitution, they could hold a referendum on the new law, if they could gather enough signatures by a late-summer deadline. Missourians—not their representatives in the legislature—would be able to decide whether to keep the 8-week ban or overturn it.

But before the advocates could begin collecting signatures, their petition needed to go through a thicket of red tape. Secretary of State Jay Ashcroft first had to approve its language, then publish an “official ballot title” containing brief summaries of the initiative and its potential fiscal impact. Ashcroft, an abortion opponent, declined to approve the petition until a court ordered him to do so. Then he took the maximum allotted time to publish the remaining paperwork, finally releasing it in mid-August. By then, supporters had just 14 days left to collect 107,510 signatures.

Of course, they couldn’t. It was an impossible task. The initiative never made it to the ballot. Three years later—too late to matter for the election—the state Supreme Court ruled that the procedural hurdles in the referendum process had violated the state constitution.

Now, pro-choice advocates in Missouri are fighting once more to put abortion on the ballot, proposing a constitutional amendment that would guarantee not just a right to abortion but also to “reproductive freedom”—the right to make one’s own decisions about contraception, prenatal and postpartum health care, and birthing conditions. In response, state officials are back to their old tricks, using the same obstruct-and-delay tactics that worked before. So far, the ballot initiative process has been delayed for two and a half months, mostly thanks to the actions of Ashcroft and Attorney General Andrew Bailey. And on top of the bureaucratic roadblocks, the state legislature is expected next year to try to make it harder to amend the state constitution.

The Missouri government’s tactics come as ballot initiatives have emerged as one of the most promising strategies to restore abortion rights. As a form of direct democracy, they offer a path to circumvent state legislatures captured by Republican gerrymandering. Nationwide, abortion access is very popular—especially since the Dobbs decision. Over the last year, 15 states have banned virtually all abortions, with devastating consequences for maternal health, not to mention pregnant people’s autonomy. Perhaps as a result, in each of the seven states that considered abortion-related ballot measures last year, voters came down on the pro-choice side. That includes conservative Kentucky and Kansas, where voters rejected bids to put no-right-to-abortion clauses in their state constitutions.

Next year, voters in an additional eight states could see an abortion-rights measure on their ballot, according to Chris Melody Fields Figueredo, executive director of the liberal-leaning Ballot Initiative Strategy Center. On top of Missouri, initiatives have so far been filed in Florida, Maryland, and South Dakota. Two weeks ago, in Ohio—where legislators are trying to make it harder to change the state constitution—supporters of an abortion-rights effort say they submitted nearly twice the number of signatures they needed to get an amendment on the 2023 ballot.

“What 2022 revealed is: This is an issue that transcends party lines,” Fields says. “What the majority of people want in a state is often in conflict with our representatives and government. So there’s a unique opportunity to move a proactive agenda around reproductive rights.”

In Missouri, it seems, many Republican politicians are reading the writing on the wall. “I think we all believe that an initiative petition will be brought forth to allow choice,” state House Speaker Dean Plocher told the Kansas City Star in May. “I believe it will pass. Absolutely.”

But not if they can stop it from reaching the ballot in the first place.

Missouri’s 8-week abortion ban from 2019—which was ultimately blocked by a federal court—now seems almost quaint compared to the total ban the state enacted last June, the same day as the Supreme Court’s Dobbs decision. Doctors who violate it face 5 to 15 years in prison. And the only exception is for medical emergencies, a category so poorly defined that hospitals have turned away some women with severe pregnancy complications.

By enshrining a right to abortion in the state constitution—the highest law in the state of Missouri—advocates intend to supersede the current ban, which was enacted by legislators. Their first step: the same paperwork process the 2019 ballot initiative got stuck in.

As part of their effort, retired pediatrician Anna Fitz-James filed multiple ballot initiative petitions with the secretary of state in March. At that point, the secretary of state is supposed to draft a summary of each petition, while the state auditor produces a fiscal note estimating its economic impact. (These blurbs, not the actual text of the proposed amendment, are the only thing voters see at the ballot box). Both summary and fiscal note must next be certified by the attorney general. Then the secretary of state publishes them along with the “official ballot title.” Only then can supporters start collecting signatures.

Bailey—who was appointed Missouri attorney general in November after former AG Eric Schmitt won a seat in the US Senate—has refused to carry out the routine step of approving the fiscal note. The process usually involves little more than making sure the blurb is less than 50 words and doesn’t contain biased language. Back in March, state Auditor Scott Fitzpatrick had surveyed state agencies and concluded that the reproductive freedom amendment would produce “no costs or savings” for the state government, except for in a single county that claimed it would lose revenue from aborted potential taxpayers. Yet Bailey insisted Fitzpatrick inflate the figure to the billions, on the baseless theory that the amendment would cause Missouri to lose federal Medicaid funding.

Fitzpatrick objected, informing Bailey that every state agency that works on Medicaid disagreed with his hypothesis. “My personal pro-life stance…is very public,” Fitzpatrick, also a Republican, wrote to Bailey in April. “As much as I would prefer to be able to say this [initiative petition] would result in a loss to the state of Missouri of $12.5 billion in federal funds, it wouldn’t. To submit a fiscal note summary that I know contains inaccurate information would violate my duty as State Auditor.”

Since then, the fiscal note has been at an impasse: Bailey won’t certify it, Fitzpatrick won’t cave, and there’s no other route for the process to move forward. “The law doesn’t even contemplate that we’d be in this situation,” says Tony Rothert, advocacy director for the ACLU of Missouri. “And what has happened is, no one has done anything.” In May, the ACLU of Missouri filed a lawsuit against Bailey, trying to get a court to force him to approve Fitzpatrick’s original estimate. Last month, a lower court agreed, ordering Bailey to certify the fiscal note. Yet when Bailey appealed, he was allowed to wait for a state Supreme Court hearing, which is set for July 18. “As long as I’m Attorney General, my office will continue to use every tool at its disposal to protect the unborn,” Bailey said in a press release earlier this month. “Our children are worth the fight.”

Mallory Schwarz, executive director of Abortion Action Missouri, sees it a different way. “Our state leadership is scared of the people,” Schwarz says. “The only way they can further try to exercise power and control over Missourians is by putting up these unfounded, unconstitutional attacks on the ballot process.”

Bailey’s expansive view of his own authority to block the abortion-rights initiative from moving forward is part of a pattern since he was elevated from his job as a lawyer in Gov. Mike Parson’s office. Relatively unknown in political circles, Bailey quickly began staking out hard-right positions, building a reputation as a conservative firebrand, and preparing to run for attorney general in 2024 against a primary challenge from a Republican activist.

In April, he issued an “emergency regulation” that—if it had been allowed to take effect—would have wiped out access to transgender healthcare not just for Missouri minors, but also trans adults. His authority to ban this care, Bailey claimed, came from the state’s Merchandising Practices Act, which allowed him to issue rules to prevent fraud. The state court wasn’t buying it. A St. Louis judge swiftly blocked the regulation, and Bailey soon dropped it. Then, in June, he opened another front in the attention war: filing an unprecedented motion asking a state appeals court to reverse the jury conviction of a white police officer who had shot and killed a Black man.

“He has tried to push the office’s powers in ways that, at least within modern memory, no attorney general has attempted to do, and it’s always been to stake out an extreme right-wing position,” says Peverill Squire, a political science professor at the University of Missouri. “It’s politically expedient for him. It does gain him the attention of political activists and the Republican Party.”

While Bailey refuses to move the fiscal note for the abortion-rights ballot initiative, secretary of state Ashcroft, who is running for governor—has been throwing up hurdles of his own to the amendment process. Ashcroft, who is charged with describing the proposed amendments to voters, produced summaries stating that they would permit “dangerous, unregulated, and unrestricted abortion.” In response, the ACLU of Missouri has filed additional lawsuits arguing Ashcroft’s summaries are “unfair” and “deceptive.” The organization has asked the courts to issue new ones that more accurately characterize the amendments.

According to Schwarz, the lawsuits against Ashcroft will also need to be resolved before supporters of the amendment can even decide to push forward with their effort. That means the petitions could be delayed far beyond the July 18 Supreme Court hearing. “If the courts come back and allow the state to intentionally misrepresent the impact of the policies and retain language like ‘dangerous’ and ‘unregulated’ abortion—which is not an accurate description of what the policies would do—then we would expect that even the most pro-choice, abortion supportive voters may not vote for that,” Schwarz explains. “It’s hard to see how Ashcroft didn’t intentionally set himself up for these legal challenges,” she adds, “likely, again, as part of an intentional effort to delay the process.”

Signatures are due next spring. So despite the delay, the ballot initiative is still on track. Yet as Rothert says, “every week of delay means it would cost more to collect signatures, and the feasibility of doing so is less.”

Republicans in the Missouri legislature have been trying to make it harder to pass ballot initiatives since at least 2018, when voters successfully used the process to repeal a right-to-work law, raise the minimum wage, and limit gerrymandering. Two years later, a ballot initiative successfully expanded Medicaid. The sequence of progressive victories sparked pushback from state politicians, says Richard von Glahn, political director of Missouri Jobs with Justice, who has been working on ballot initiative campaigns in the state since 2006. “We started seeing legislation popping up to curtail this process that has existed in Missouri for over 100 years,” von Glahn says.

Since 2021, Missouri legislators have introduced 71 bills to change the initiative process according to data from the Ballot Initiative Strategy Center. Some proposals would have increased the number of signatures needed for a successful petition, or required a supermajority vote to approve an initiative. Another proposal would require amendments to win not just the popular vote, but the majority of congressional districts, putting outsized power in the hands of rural residents.

So far, none of the bills have passed. One recent deal to raise the vote threshold to amend the constitution died in the state Senate. Yet Majority Leader Cindy O’Laughlin reportedly wrote in a constituent newsletter that her colleagues intend to push for new changes to the initiative process next year, ahead of a statewide vote on abortion. “The threat of abortion with no restrictions looms large and we are committed to finding the answer early next year,” she wrote.

Supporters of the constitutional amendment aren’t yet sure which version they’re going to campaign to put on the ballot. Because voters on Election Day only see the secretary of state’s summary and the state auditor’s fiscal note—not the actual text of the proposed amendment—it’s typical for campaigners to file many different versions, wait for the summaries to be issued, and then research which one will most appeal to voters. They gather signatures for that one and drop the others, explains von Glahn, the veteran ballot initiative strategist.

All 11 versions of the abortion-rights initiative would add the right to reproductive freedom to the state constitution. In addition, they mix-and-match a range of additional clauses, which moderate abortion rights to a greater or lesser degree. Some permit the legislature to ban abortion after 24 weeks, or fetal viability. Others allow for laws that would require parental consent for most minors’ abortions. Yet more state that the amendment does not require government funding for abortions.

“We’ll have to get everyone together who cares about the issue, all the stakeholders, and hear from them about what’s most important,” Rothert says. “It’s no secret no one wants to put a measure on the ballot that is going to fail. So there will have to be some polling to make sure that a measure is viable before you go to the expense and trouble of trying to get it on the ballot.”

The reality is that, even before Dobbs, abortion access in Missouri was close to nil. The legislature had passed too many burdensome and medically unnecessary rules designed to be impossible for abortion clinics to comply with. In the years prior to Dobbs, the only clinic still offering abortions was a Planned Parenthood location in St. Louis, which performed about 100 abortions annually.

“Many, many Missourians for years now have gone to Kansas or Illinois to access care, because the states had fewer restrictions,” explains Emily Wales, CEO of Planned Parenthood Great Plains, which stopped offering abortions at its Missouri locations in 2018. Before Dobbs, her organization’s Kansas clinics served patients in their state as well as those traveling from Missouri. Now, they’re also seeing people travel to Kansas from Texas, Arkansas, Louisiana, and Alabama. “The regional nature of care was strained and difficult before the loss of Roe, but since that time, the system is completely broken,” Wales says. “We do not have anywhere near the appointments needed to support all of the people across the region.”

Even if the abortion-rights amendment were to pass next year, the restrictions from the past would remain on the books, making it difficult for abortion clinics to immediately reopen.

“It is clear that we cannot rebuild Roe: a system under which patients were routinely denied access to care—where abortion was a right on paper only,” Colleen McNicholas, chief medical officer of Planned Parenthood of the St. Louis Region and Southwest Missouri, says in a written statement. “We continue to work with partners to demand that restored access in Missouri is meaningful access—meaningful in a way that Missourians have not seen in decades.”

According to Schwarz, putting a right to abortion in the constitution is just first step. She believes it could allow new clinics to come to Missouri. But on top of that, it’s geared to lay the groundwork for future legal challenges to the old restrictions. “It will take the collective efforts of advocates and lawyers and providers working in concert to challenge the laws that have existed for decades,” Schwarz says.

Correction, July 18: An earlier version of this story misstated which organization counted how many bills Missouri legislators introduced to change the ballot initiative process. It was the Ballot Initiative Strategy Center.