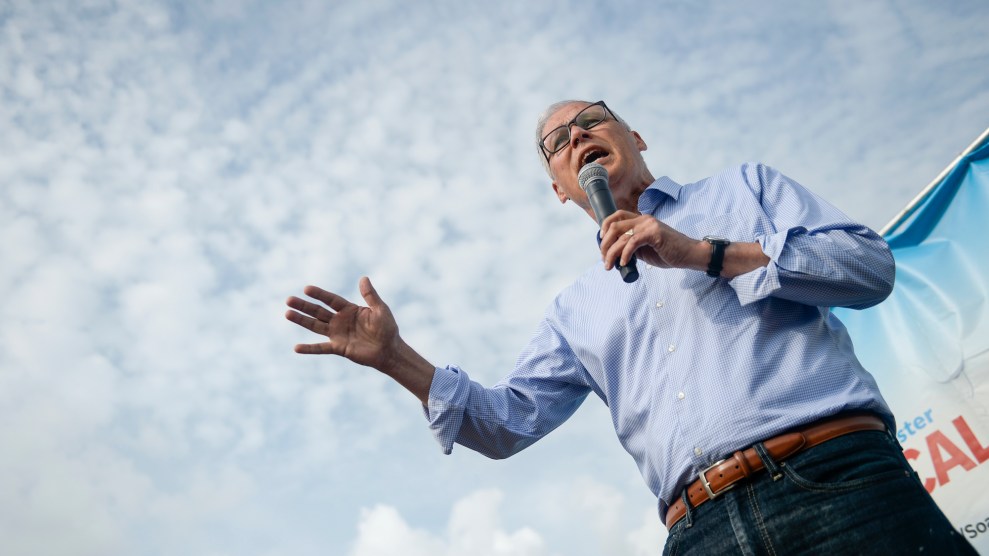

Caroline Brehman/Associated Press

True to his fixation on battling climate change, today Washington governor and Democratic presidential hopeful Jay Inslee released a rural policy platform centered on encouraging farmers to pull carbon from the atmosphere and trap it in soil.

For decades, United States farm policy has pushed farmers in the nation’s Midwestern states to maximize production of corn and soybeans, even during prolonged periods of low prices. The result: Millions of acres of some of the globes most fertile farmland have been exposed to catastrophic soil erosion and vulnerable to climate shocks like droughts and heavy spring rains.

Here’s how Inslee’s plan, released Wednesday morning, would shake things up on the climate front:

• Transform federal crop insurance. Taxpayers currently spend at least $7 billion annually subsidizing crop insurance—a major linchpin propping up the corn-soybean duopoly. Inslee proposes to require the program to “account for climate risk in its actuarial tables.” That would likely penalize the Midwest’s farmers who leave their land bare all winter, which exposes it to damage from severe storms like the ones that hit this year.

• Pay farmers for “carbon farming.” Currently, the great bulk of farm programs reward growers for churning out as much crop as possible, even when prices are low, leading to big gluts—along with soil erosion and polluted water. Inslee wants to give farmers a different goal: sequester as much carbon as possible. As I show here, diverse cash crop rotations, use of winter-season cover crops, and limited tillage allow farmers to pull carbon from the atmosphere and store it in soil.

Using such practices, farmers can bring up the organic matter content in their soil from “1 to 2 percent up to 5 to 8 percent over ten or more years,” enough to transfer as much as 60 tons of carbon per acre from the atmosphere into the ground, according to Project Drawdown (which the Inslee plan cites). He plans to pay farmers (an unspecified amount) for making the journey. Carbon-rich soils capture and hold more water, buffering the flood potential of heavy rains and making land more resilient to droughts. Those same practices will also “reduce the use of petrochemical fertilizers and pesticides, and protect pollinators—all of which are crucial to sustaining and rebuilding healthy soils and ecosystems,” the plan states.

• Invest big in research to help farmers sequester carbon and adapt to climate change. Inslee wants to create an R&D wing within the US Department of Agriculture modeled on the Department of Defense’s Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA), which incubated the internet. The program, dubbed ARPA-Ag, would “research crops and farming practices that maximize the potential to provide long-term natural carbon storage that makes a lasting contribution to cleaning the atmosphere,” the plan states. Inslee’s plan would put a new “ARPA-Ag” department at the center of a plan to “at least triple annual federal agricultural R&D investment” and direct research “into sustainable, organic, and regenerative agriculture.”

While the Trump administration has brazenly downplayed the USDA’s climate research, Inslee would direct the department to “adopt comprehensive five- and ten-year plans focused on climate change, food supplies, and the related global challenges, and expanding investment in USDA’s regional Climate Hubs.”

In presidential elections since the Great Depression, food policy has been a marginal concern. This year, candidates’ policy teams are putting real thought into it. In March, Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D.-Mass.) came out with an ag platform centered on busting up the handful of gigantic seed, pesticide, fertilizer, and grain-trading companies that claim the bulk of profits from agriculture, leaving farmers scrambling for crumbs.

In May, Sen. Bernie Sanders (I.-Vermont) released an ag platform that matched Warren’s in trust-busting zeal, and added a wrinkle. I described it at the time:

It includes a remedy that hearkens back to the New Deal era: a proposal to help farmers of big commodity crops like corn and soybeans coordinate planting decisions to avoid chronic overproduction. This policy is known as supply management. He would reestablish a national grain reserve, a lapsed New Deal institution that collected excess crops in bountiful years to keep prices from plunging, and release them in bad years to avoid shortages (a notion that, as Sanders points out, makes lots of sense in an era of climate chaos). No major candidate since Jesse Jackson, who ran during the height of a brutal farm crisis in the 1980s, has proposed supply management, according to Iowa corn and soybean farmer and long-time rural activist George Naylor.

And in early August, Warren returned to the fray by rolling out her vision for completely overhauling US farm policy. She proposed a supply management plan to match Sanders’; a dramatic expansion of spending to pay farmers for soil-building practices like cover crops; and a $1 billion “Farm to People” program in which all federally-supported public institutions—like public schools, military bases and hospitals— “will partner with local, independent farmers to provide fresh, local food.”

Even front-runner Joe Biden, the ultimate establishment Democrat, recently put out a “plan for rural America” that mentions antitrust and vows to “ensure our agricultural sector is the first in the world to achieve net-zero emissions.”

On September 4, 10 Democratic candidates will participate in a Climate Crisis Town Hall. With all of this fervor around agriculture policy, perhaps they’ll take the opportunity to debate the issue then. Unfortunately, Inslee—who pushed hard for the forum—probably won’t attend, because he seems likely to miss CNN’s threshold of reaching 2 percent support in at least four Democratic National Committee-approved polls conducted between June 28 and Aug. 21.

This post has been updated.