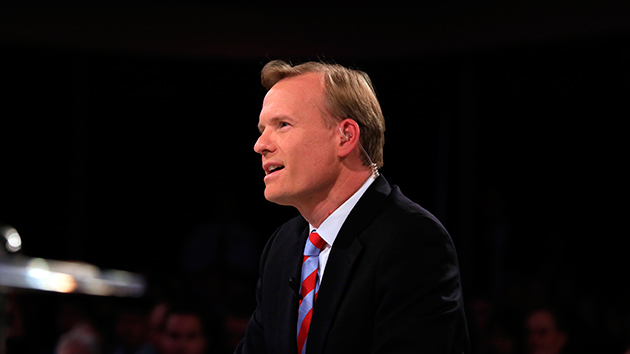

The second Democratic presidential debate of the 2016 race had one clear winner—the moderator, John Dickerson. The longtime Slate political correspondent—who co-hosts the Political Gabfest podcast and recently took over as host of Face the Nation on CBS—was “the only star of the show” (The Daily Beast), and won plaudits for his “ferret-like journalistic questioning” (Politico) without making the show about himself.

But Dickerson’s pointed queries and tough follow-ups should come as no surprise. John Dickerson is a political junkie’s political junkie. He brings that same curiosity and attention to detail to yet another podcast: Whistlestop. This weekly gem is his obsessively researched dive into the dramas of campaigns past—forgotten and otherwise. Whether the subject is George Romney’s last campaign, Grover Cleveland’s love child, or the historical precedent for Donald Trump, the man has got you covered.

Mother Jones: How do you find the time to keep doing Whistlestop when you’re juggling so many other jobs?

John Dickerson: It’s fun! I love history. I love the human drama. And when you do something fun, it unlocks lots of other ideas in other areas of your work life. It’s also a way for me to think about changing standards in campaigns and public life—what do we expect from our politicians and from our press and from the voters? And it’s an antidote to the scandal or gaffe of the moment that has consumed so much of our political coverage.

MJ: How do you prep for it?

JD: I have a set of books on presidential campaigns. So whatever topic I’m writing about, I look through those books to re-familiarize myself. Then I have a researcher who goes into the archives and collects relevant newspaper clippings—I’ve done Whistle Stops on the races in 1840 and 1884, so I get a bunch of PDFs of the newspapers of the time. If there’s anybody living who was a part of these stories, I sometimes call them. I interviewed Clark Hoyt, a newspaperman for the Knight chain in 1972 when Thomas Eagleton was put on [George] McGovern’s ticket—he co-wrote the Pulitzer Prize-winning piece about Eagle-ton and electric-shock therapy. I do all of that, and then make a huge outline and start writing.

MJ: So what are some campaign books we should all check out from the library right this instant?

JD: Fear and Loathing is a great book. Boys on the Bus is very good. See How They Ran, Gil Troy’s book about the changing nature of US presidential campaigns, even though it’s not about one campaign, is really great. The Invisible Bridge, by Rick Perlstein, about Reagan and the rise of the conservative movement has got that big sweep of history. The Roots of Modern Conservatism has been a great book about Eisenhower and Taft and all the fights in the ’50s that sound very familiar today. What It Takes is a great book. I could go on.

MJ: I noticed you Whistlestopped both of Reagan’s campaigns.

JD: Well, in 1976, taking on an incumbent of his own party to make for the first incumbent since Chester Arthur who was not re-nominated was a signature event. Also, Reagan is to the conservative movement what FDR and Kennedy are to the Democratic Party. He’s such a lionized figure. I spend a lot of time with Republicans and you hear about him a lot. You think of him as being this glamorous, flawless performer, but then when you look at him campaigning, there are times when he’s just really clunky.

MJ: What are you looking for in your research?

JD: I’m looking for color and something that gives a sense of the moment, a sense of the theatrical “you are there” kind of feeling. Details about a specific event, or sometimes just the way people talked at the time. Before the election of 1884—I was doing a Whistlestop on James G. Blaine—there was an investigation by the House Judiciary Committee, and the transcript of that exists. It was fun to read the way they discussed this corruption charge because the language is antiquated and the back-and-forth is entertaining. And then I’m looking for context—anything that can make a larger point about that candidate or the way campaigns have evolved.

MJ: Some might liken Blaine’s scandals to the Clinton emails.

JD: He tried to destroy a letter. There’s no proof that Hillary Clinton destroyed anything. But she tried to limit the amount of contact with her emails that investigators could have, and that’s certainly what Blaine was trying to do. Partisans would say Clinton is just like Blaine, but that’s not true. Blaine was allegedly made quite wealthy by using his influence to help the railroad companies and then getting paid by people involved with the companies. Nobody now would be able to get away with those kinds of things.

MJ: What else has changed?

JD: The speed of the conversation. It’s really amazing how fast the news cycles turn. What’s different is the potential for things to go shooting off in another direction at any moment. What’s so striking about the Eagleton affair is that his vice presidential dreams were over in 18 days, which seems incredibly fast, particularly for 1972. Today, he might not even last half a week. I mean, it’s weird; there’s an intolerance for foibles and the roughness of people’s lives. Cleveland would be just doomed.

MJ: Yeah, I was just re-listening to your episode on Grover Cleveland, whose insane presidential run revolved around a wild paternity case. Have our candidates gotten more boring?

JD: At least outwardly. If a candidate had an out-of-wedlock child, the press would go nuts. But we don’t go hunting for that kind of stuff. In Cleveland’s case, there was this rumor. He admitted it and off they went. In today’s world, somebody like Blaine—who had the stink of corruption around him—wouldn’t get very far.

MJ: So is there any historical precedent for a candidate like Donald Trump?

JD: No one who has the kind of throw weight that he does. Morry Taylor ran as a businessman in 1996, and of course Herman Cain ran as a businessman last time. Trump is unlikely to be president, but he’s going to bounce things around a lot more than Taylor ever did.

MJ: One might put Trump into the class of folks running to get attention and sell books. How recent is that sort of thing?

JD: I don’t think we had it before, other than novelty candidates who are comedians or something. It wasn’t until the primary system of the ’60s—maybe you could go all the way back to Eisenhower in ’52—that you could find a way around the party structure that screened out these kinds of people. But Eisenhower was a war hero. You don’t have to be a war hero now. If you have the money and a way to whip up the primary voters, anybody can do it.

MJ: Is there any past election you’ve found particularly helpful in understanding this one?

JD: The election of 1840 and its crazy circuslike atmosphere sure feels like a Trump rally. And Ross Perot’s claims of the power of business acumen to completely change the face of government reminds you of Trump. The election of 1992 and the way talk shows changed the relationship between candidates and the media feel a little like the changes taking place from social media today.

MJ: I’m curious how your interest in past campaigns informs your approach as host of Face the Nation.

JD: I try to have a sense of history in picking out things happening now that might actually have historical import. Like what current events are going to be worth talking about in 20 years, and are we paying enough attention to them? I also try to take what some people think is new and say, “This is a part of a historical pattern; it represents tensions that have been part of the American system for a long time.” For example, the debates between conservatives and moderates in the Republican Party has been going on since Eisenhower and Taft—different issues. What was called conservative back in 1952 would be kind of middle-of-the-road now. But the battles between the two, and the way tactical disagreements are elevated into ideological ones—the script is very familiar. And so that gives you a little perspective when people are freaking about unprecedented behavior. It’s actually not that unprecedented.

MJ: What do you miss most about the elections of yore?

JD: The way candidates talked was a lot more interesting. It wasn’t that they were being honest, but they were more forthright. And candidates talked a lot—they talked to reporters and their speeches were risky. Everything wasn’t so pre-packaged. Also, the electorate was less polarized, so you didn’t have people just signing up as, “Oh, he’s a Republican. I’m going to vote for him.” There was a real fight at stake for those in-the-middle voters—who don’t exist in as great numbers now as they did back then. And I would love us to return to a time when candidates offered arguments for their candidacy based on facts and history, and not just a string of assertions.

MJ: Has the relentless pace of modern campaigns made it harder to identify those game-changing moments—like Ed Muskie crying on the campaign trail?

JD: Well, “47 percent” for Mitt Romney: Fifty years from now, that would be a good item for Whistlestop. He may have been doomed even before that, but it’s a turning point in the campaign. It’s also a story about technology. It’s a story, arguably, about fundraising; he was at a fundraiser, which distorts how you talk as a candidate. It’s a story about the economy and the extent to which outsourcing became a huge source of American economic insecurity in the 2000s. So there are a lot of big themes that are a part of that 47 percent videotape. It can still happen.