Ted S. Warren/AP

It was a debate in 2016, and it rages today: Can a self-proclaimed socialist win a presidential election? Bernie Sanders and his supporters enthusiastically proclaim yes. But there is no overwhelming empirical evidence to support their view. After all, it has never happened before. And a recent poll shows that socialism, while popular within limited segments of the American public, still has a negative impression across most of the population. Sanders and his fans point to polls for the 2016 race and the 2020 contests that have showed Sanders beating Donald Trump. But these polls all have been conducted within an unusual context: no negative ads blasting Sanders for being a socialist. That is, Sanders has never been on the receiving end of a nationwide blitz of attack ads that denounce him for being a socialist and that assail him for additional unorthodox stances he has taken.

This is why Sanders and his backers should at this stage welcome negative ads that attempt to delegitimize him. That would demonstrate whether they are right—and whether Sanders can withstand such a pummeling.

Of course, this suggestion is made somewhat facetiously. No candidate has ever invited an assault on himself or herself. But that would be the only way to test the Sanders camp’s contention that his embrace of democratic socialism will not be a serious vulnerability, should Sanders bag the Democratic Party’s presidential nomination. There is little doubt that were he to become the Dems’ standard bearer, Sanders will likely be met with half-a-billion dollars (maybe more) in ads that depict him as a wild-eyed socialist who honeymooned in Moscow and expressed out-of-the-mainstream opinions on sexual freedom and other subjects. In 2016 and the current race so far, Sanders has not had to confront such a blast.

Sanders’ top strategists tend to wave off the socialism issue. Recently Jeffrey Weaver, a longtime Sanders adviser, told me this is no problem for Sanders. Republicans, he said, “call every Democratic a socialist, and they spend a lot of time fighting that charge. We’re not going to have that argument—whether you’re a socialist or not. Instead, Sanders can talk about how Donald Trump wants to cut Social Security and take healthcare away and give tax cuts to people who don’t deserve them.” Weaver is suggesting that Sanders can defuse this classic right-wing line-of-attack by conceding the point: Yeah, I’m a socialist.

But is that being optimistic? Sanders can make this all go away so easily? Weaver insisted that Sanders could “ju-jitsu” the you’re-a-socialist slam by talking about Trump’s “corporate socialism.” He pointed out that when Sanders ran for US Senate in 2006, his GOP opponent took out ads that essentially called Sanders a friend of terrorists and child-molesters. (Sanders had voted against mandatory minimum sentences). Yet Sanders won. By that point, though, Sanders had represented Vermont in the House of Representatives as a democratic socialist for a decade and a half.

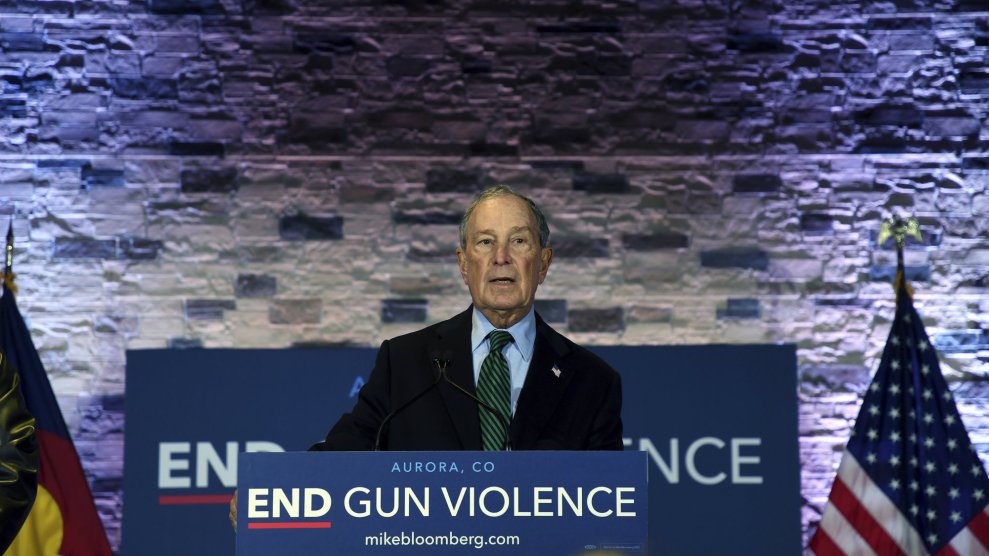

In short, Weaver maintained that generously financed scare-ads would simply bounce off Sanders. “You go to the American people and take the money out of this. Bernie is one of the most well-defined figures in American politics. If you ask voters, what they think of him, they say, Medicare For All, he’s for the working class and the little guy. They don’t say he’s a socialist.” And in a dig at former New York City Mayor Mike Bloomberg, he added, “Democratic socialism is far less problematic for people than taking away the soda they want to drink.”

But can any candidate just side-step the fight to define his or her public image? Even well-known hopefuls often have to deal with vicious campaigns that seek to influence how they are perceived by voters. Will an everybody-knows-I’m-a-socialist response do the trick, when ads raise questions about Sanders’ patriotism and assail his attitude toward free enterprise? Remember, these ads don’t have to be accurate. (They could, for instance, show Sanders praising Nicaraguan dictator Daniel Ortega—years before Ortega, a leftist, went all-out authoritarian.) And while it is true that Trump and the Republicans will claim any Democratic nominee is a “socialist” who despises the American way of life, might such attacks hit harder if a Democrats retorts, “I am a socialist, but I’m a democratic socialist”? (Which to some might sound like Democratic socialist.)

Despite what Weaver argues, Sanders is probably not invulnerable in this regard. One recent Yahoo/YouGov poll noted that 62 percent of registered voters know that Sanders is a socialist. (Eighteen percent said he isn’t; a fifth were unsure.) But that poll also found that 47 percent had an unfavorable view of socialism, though only 26 percent had a positive impression. Meanwhile, 38 percent said that “socialism” is the same thing as “democratic socialism”—the label Sanders wears. (A quarter of respondents were uncertain if they are the same.) These margins do appear to give Trump’s ad-makers material to work with.

In the absence of a negative fusillade, it’s impossible to state that Sanders will fare best—or even competitively—against Trump. It can only be a hunch. Other Democratic candidates have already encountered fierce Republican efforts to discredit them. Trump and his GOP handmaids turned Trump’s impeachment into a high-profile attack on former Vice President Joe Biden. Previously, Trump trained his tweeting firepower on Sen. Elizabeth Warren. But Sanders waltzed through the 2016 campaign with no barrage of negative ads from the Hillary Clinton forces. And though his Democratic rivals have taken jabs at him at the debates during the 2020 contest, there has been no bombardment. In one debate, when the Democratic wannabes were asked if Sanders’ democratic socialism could be a problem for their party in a general election, only Sen. Amy Klobuchar raised her hand; that was hardly a blistering denunciation. (Bloomberg, too, has so far gotten off easy. But that may change as he becomes a participant in the Democratic debates.)

It’s long been an axiom of American politics that it’s better to be attacked earlier in a race than later. This gives a candidate time to figure out how best to reply and a chance to turn potential controversies into old news by Election Day. It also offers voters a chance to see how a candidate can perform under fire and handle the incoming. As of now, one cannot definitively determine if devoting hundreds of millions of dollars to vilifying Sanders as a socialist will be effective—or be a waste of money. If his Democratic foes were spending millions in such a manner, that might yield data that could be useful in assessing how the issue would play out in the general election. But that’s not happening.

For Sanders and his team, the only way to prove that he can withstand such an onslaught and go on to victory is to…withstand such an onslaught. But that assault may only occur if Sanders becomes the Democrat to challenge Trump in the fall. So for the time being, the arguments and assurances that Sanders’ socialism is no liability for Trump to exploit are merely beliefs and wishes. And the head-to-head polls matching Sanders and Trump ought to be heavily caveated. The electability of a socialist presidential candidate in the United States remains one big political science experiment, the possible results of which—without a test run—are open to guessing and never-ending debate.